Word & Image

Juried by Caroline Goldstein

About the Juror

Caroline Goldstein is Currently the Managing Editor for Artnet. Goldstein has written art news for W magazine, Muckrack and other digital magazines. Goldstein worked at Osmos Gallery and International Print Center NY. She graduated from Sotheby's Institute of Art The Graduate School of Art and Its Markets in London and NYC, Corcoran School of the Arts and Design at The George Washington University

Curatorial Statement

When I embarked on the jury process for this show, I had a vague notion of what kind of word-based art I would encounter, after all, the history of art is very much a history of text in art, and text as art. What I came across in the hundreds of submissions exceeded my expectations. The works literally spoke to me, and so too, did the artists who created them.

Some might wonder why bother incorporating words into art, when we all know that a picture is worth a thousand words. But that hierarchical statement leaves no room for the rich relationship between what is seen and what is spoken, for the interplay of visual and verbal elements whether in tune or at odds with one another. Hieroglyphics in ancient Egypt, traditional Chinese calligraphy, and illuminated manuscripts are some of the earliest examples of text and image used in tandem as a narrative device to enhance meaning and reach a wider audience. Things really got interesting in the 20th century, when Cubists sought to buck conventions, rejecting the notion that art should seek to faithfully represent nature, instead seeking a disjointed, fractured visual language to reflect the rapidly changing modern world. It is little wonder that the movement birthed collage, where everyday materials are elevated to high art—newspaper fragments and other ephemera reconstituted as social commentary.

From there, the possibilities for incorporating text in art expanded. When Rene Magritte famously wrote ‘ceci n’est pas une pipe’ beneath a very clear illustration of a pipe, he was making a declaration about the state of representation versus reality, the dissonance between what is perceived and what is true, one that artists continue to probe to this day. More recently, artists like Jenny Holzer, the Guerrilla Girls, and Ai Weiwei have used text to needle at structures of power, both within and outside of the art world. Given the polarizing state of the world, it is no wonder that many of the works here convey a feeling of mistrust, in systems and in the words that built those systems. But alongside that erosion of trust, there is still a belief in the immense power that words have—to shape government policy, to attract a mate on a dating website, to amuse, to confess, to condemn, and to inspire, and these entries reflect that tension.

– Caroline Goldstein

Words to Live By

Patricia Autenrieth / Paige Bradley / Andrew Demirjian / Kristina Estell / Naomi Grossman / Tilde Grynnerup / Yukio Ito / Tom Gehrig

In this section, the interplay of words and images are full of hope, joy, and optimism. These words are incantations whispered, chanted, and longed for. They are deepest thoughts and yearnings made visible and tangible, and put into action. Patricia Autenrieth’s quilt emblazoned with the stitched word ‘MAMA’ spanning its entirety is an ode to motherhood. Historical motifs of femininity and domesticity—a high heeled shoe, a spatula, an iron, the seal of Good Housekeeping, a trio of ducks—are stitched throughout the fabric in the thinnest white thread, almost imperceptible, much like the often invisible labor of parenthood. Andrew Demirjian’s piece is another kind of patchwork. An image of an imaginary flag serves as the backdrop for a musical composition that remixes the final notes and lyrics from national anthems, with the goal ‘to disentangle one’s connection to a nation and notions of fixed borders.’ Tilde Grynnerup’s textile also resembles a flag, though here are simply the words ‘here we all are under the same sun.’

In Yukio Ito’s cosmic print, vibrant, luminous ribbons swirl to form the abstracted word ‘oasis,’ and Tom Gehrig also invokes the sky with depictions of constellations, where mythology was literally written in the stars. Paige Bradley’s sculpture of a supine female, arm outstretched to cradle an orb is lit from within, illuminating the word ‘breathe’ etched on her breast. Naomi Grossman’s sculptures are made from wires shaped into female figures, bound together literally and figuratively by the familiar promises of wedding vows. Kristina Estell uses high-visibility neon fabric cut to form the German word Sympatisch, meaning friendly and agreeable, is suspended from the ceiling like a visual exclamation mark.

Andrew Demirjian

Pan-terrestrial People's Anthem

Video

5.6" x 3.5"

$1,000.00

Empty Promises, Where Words Fail

Natalie Armstrong / Linda Bond / Martin Brief / Jasmine Cogan / Ranjini Chatterjee / Christina Maile / Diana Schmertz / Madeleine Soloway / Stephen Spiller / Britt Thomas / Gary Westford / Kenneth R Windsor

In this section, the artists have found the words of record to be lacking. Language that was once considered unimpeachable is now mutable.

Natalie Armstrong and Madeleine Soloway use seemingly innocuous, even appealing imagery to reframe narratives of violence, humiliations, and threats aimed at women. Armstrong’s intimate collages presented in ornate oval frames that recall 18th century keepsakes illustrate the dark fates of young women in nursery rhymes and fairytales, while Soloway’s prints of delicate, intimate garments hanging on clotheslines are marked with snippets of misogynistic and predatory language of public discourse. Stephen Spiller also taps into the fraught state of identity politics with a piece that bears the notification that a gender transition request has been denied, literal baggage that is printed on a hot pink weathered suitcase. Linda Bond and Diana Schmertz use the text of Supreme Court decisions as the foundation of their works, reflecting the fractured state of American democracy, and the threat to bodily autonomy.

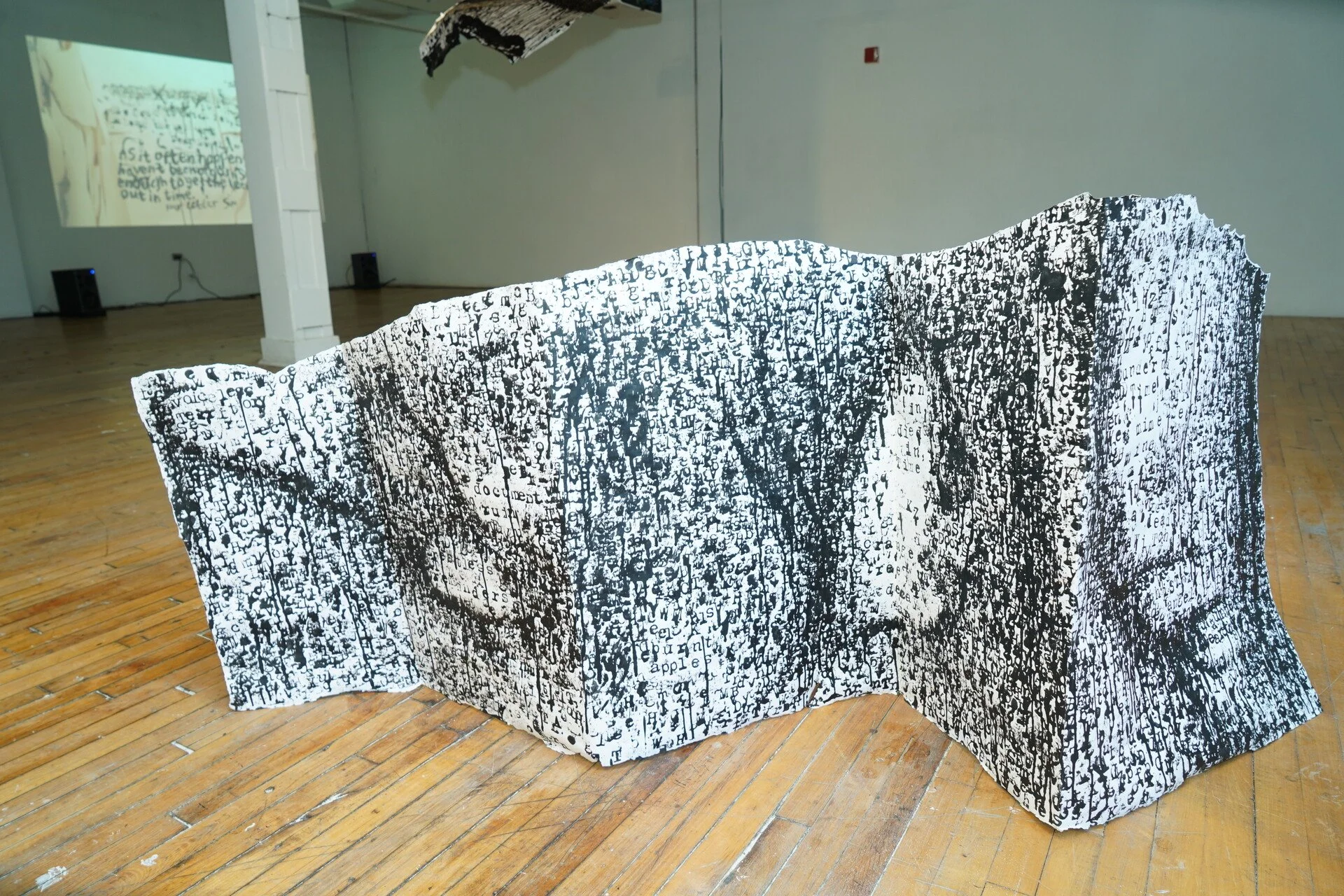

Jasmine Cogan, Gary Westford, and Kenneth R Windsor present compositions in which anodyne phrases, typically associated with positivity and resilience, are juxtaposed with biting satire, underscoring the conflicting messages of capitalism and mass media. Britt Thomas’s pun-based performances—in which the word ‘Press’ is literally pressed into the ground in a funereal procession for journalism, and artificial grass is the canvas for a commentary on the practice of ‘astroturfing’ at protests. From far away, Martin Brief’s works Declaration and Constitution appear to be abstract landscapes, perhaps depicting a vast swath of sea or sky. But in fact, they are the words of the United States’s foundational texts, handwritten and subsequently erased, scraped away with a blade.

Ranjini Chatterjee’s collage underscores the imbalance between lived experience and historical records; Christina Maile’s series of photographs from Gaza are real-time documents of lived experience in wartime accompanied by quotes

Word as Image

John Banks / Hiral Bhagat / Elizabeth Bonner / Allen Camp / Shiyun Deng / Mario F. Bocanegra Martinez / Wendy Collin Sorin / Stephanie Lanter / Barbara Lubliner / Marina Wittemann /Michael McNeil / Azita Panahpour / Christelle Lacombe / Jamie Zimchek / Cheryl Hahn / Suzette Marie Martin

Early 20th century artists sought to divorce meaning from words, experimenting with randomly placed letters and numbers jumbled and reconstituted as purely visual expressions. Here, the shape of text is prized over meaning.

Barbara Lubliner and Mario F. Bocanegra Martinez continue that tradition with overlaid text and symbols that, though static, feel urgent and dynamic. Wendy Collin Sorin’s collages are made from the detritus of consumerism; labels from cans and crates are illegible and meaningless except as recycled raw material. Hiral Bhagat composes something akin to a concrete poem, in which the typography itself is the illustration, the stylized Gujarati calligraphy organized to form a swirling composition that references the topography and rich culture of Ahmedabad. John Banks’s and Azita Panahpour’s steel sculptures take on different shapes depending on the direction from which they are viewed. What appears to be an abstract work of interconnected shapes coalesces into a legible script with a simple shift in perspective.

Stephanie Lanter’s three-dimensional text sculptures are comprised from the shards of previous works, rendered abstractly so that the text is unreadable, while Elizabeth Bonner’s ceramic sculptures take the shape of recognizable animals adorned with letters and words. Marina Wittemann’s wall sculptures beg to be touched, appearing soft and velvety, but comprised of recycled newspapers—a pastel shell covering propaganda; by contrast, Allen Camp’s painted words have been unfurled and the letters strewn about the canvas, rendered useless. Shiyun Deng harnesses the gestural movement of mark making into a rollicking and dynamic canvas, while Christelle Lacombe and Jamie Zimchek’s humble musings, doodles, and scrawls become elegant and ambiguous illustrations, serving as relic of the predigital age that recall Cy Twombly’s lyrical canvases. Cheryl Hahn and Suzette Marie Martin opt for symbols a la Hilma af Klint to reflect on the natural world and our place within it.

Flipping the Script

Robin Colodzin / Pennie Fien / Erin Galvez / Greta Benavides / Todd Gardner / Safia Fatimi / Marcia Haffmans / Kirstie Klein / Kelly Tsai / Pauline Chernichaw / David Coons / Cassandra Zampini

The artists in this section are reclaiming narratives using collage, appropriation, and found objects. Overlooked individuals, mostly female, are brought to the fore and given their due.

Robin Colodzin’s paintings of nude figures accompanied by an excerpt from John Berger’s canonical text ‘Ways of Seeing’ is a study on the pervasiveness of societal expectations for women, in which they are both objects of a steady, piercing, and unyielding gaze, and perpetrators of that same gaze upon themselves. Pennie Fien stages interventions in the pages of outdated art history texts that omitted notable female artists, correcting the historical record, and Greta Benavides has collaged the text and images from a story in the Los Angeles Times documenting a young boy’s immigration journey with original illustrations to create a wholly new work of art that is both diaristic and a record. Marcia Haffman’s work with female inmates, Living Text, bears witness to lives that are often marginalized and dismissed, the handwriting of each individual is freed from the constraints of mass incarceration.

Erin Galvez’s candy colored kaleidoscopic drawings are at odds with the words ‘cultural suicide’ repeated to create the patterns, while Todd Gardner and Cassandra Zampini’s digital collages incorporate jarring symbols of Internet and analog culture to warn of a fraying social fabric. David Coons’s line drawing is a shrewd indictment of online profiles, curated and edited to show half truths that belie the messiness of desire and self preservation, which is on full display in Pauline Chernichaw’s Bathroom Chat, documenting the latrinalia of a Lower East Side bathroom, where the morays of public communication give way to the reckless abandon of perceived anonymity and privacy. Kelly Tsai’s project SKyGiRLS spotlights women of the Asian diaspora, often misunderstood and underestimated in their time, but here reevaluated as icons of popular culture. So too, are the women depicted in portraits by Kirstie Klein and Safia Fatimi. Recalling photo series like Gillian Wearing’s “Signs that say what you want them to say not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say,” the women’s innermost thoughts are laid bare, transformed from invisible scars to painted facts.

Cassandra Zampini

MediaWarfare

Video

Iconography of the Everyday

Jenny Balisle / Leela Cormon / Ellen Mahaffy / Elias Mendel / Reineke Hollander / Claudia Doring Baez / Daniel Kingery / Geoffrey Stein / Christos Pantieras / Midori Midori / Sol Hill / Elizabeth Bennett

There is a long history of artists turning to everyday materials and elevating them to so-called ‘high art.’ Here, those objects and scenes are culled from pop culture, personal archives, and communal

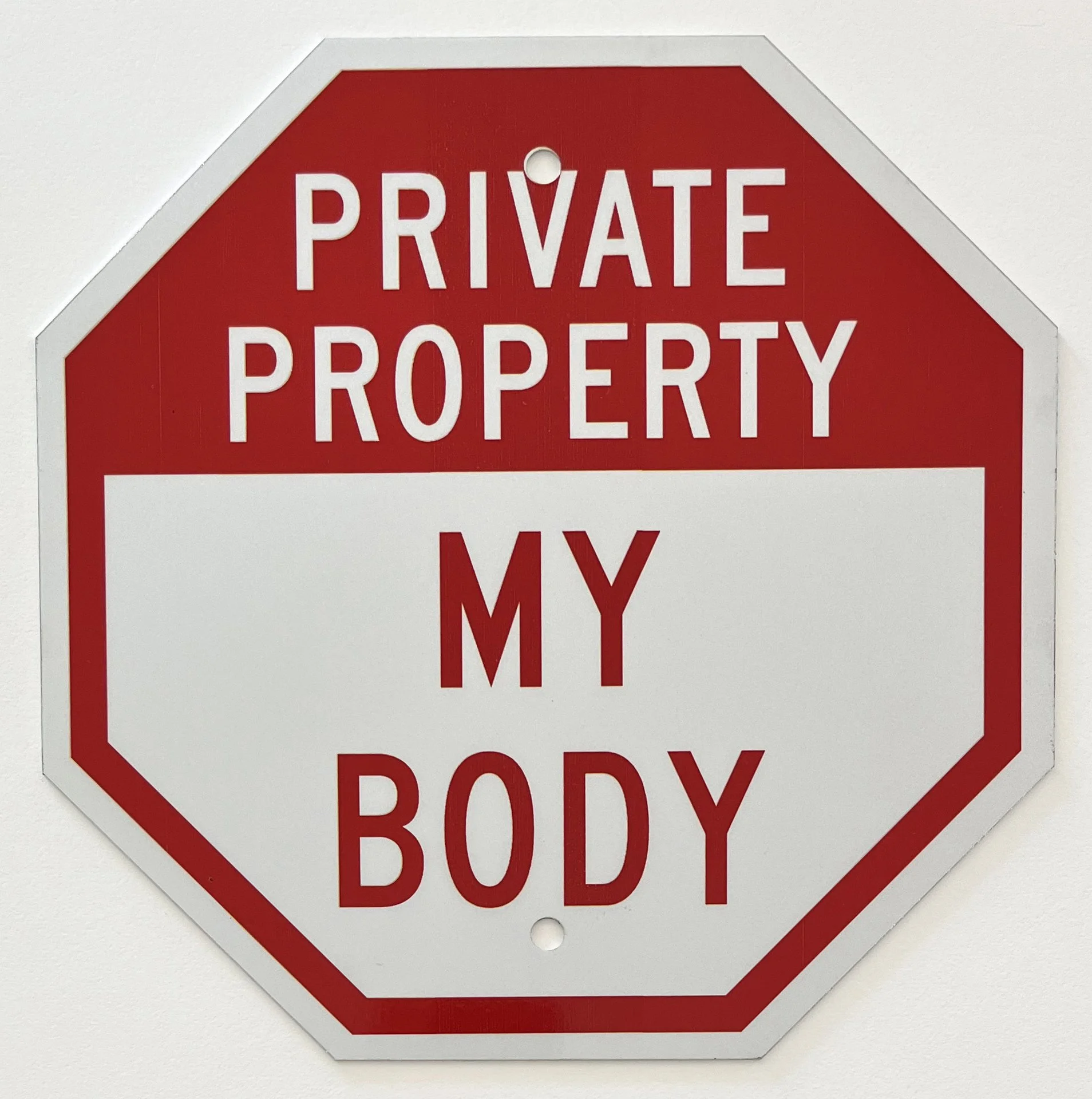

Jenny Balisle uses the familiar iconography of a red and white traffic sign to declare ‘my body’ as private property, serving as a commentary on the rules and bureaucracy that are imposed on personal choices. Leela Cormon employs the format of a graphic novel, using illustrated panels and text to spin a self-portrait of a complex mother daughter relationship; and Ellen Mahaffy, Elias Mendel, and Reineke Hollander mine vintage archives for relics of the past that speak to the current moment. In Michael McFadden’s collages, gay porn, hunting, and gardening magazines are spliced and sewn together to offer a layered and complex portrait.

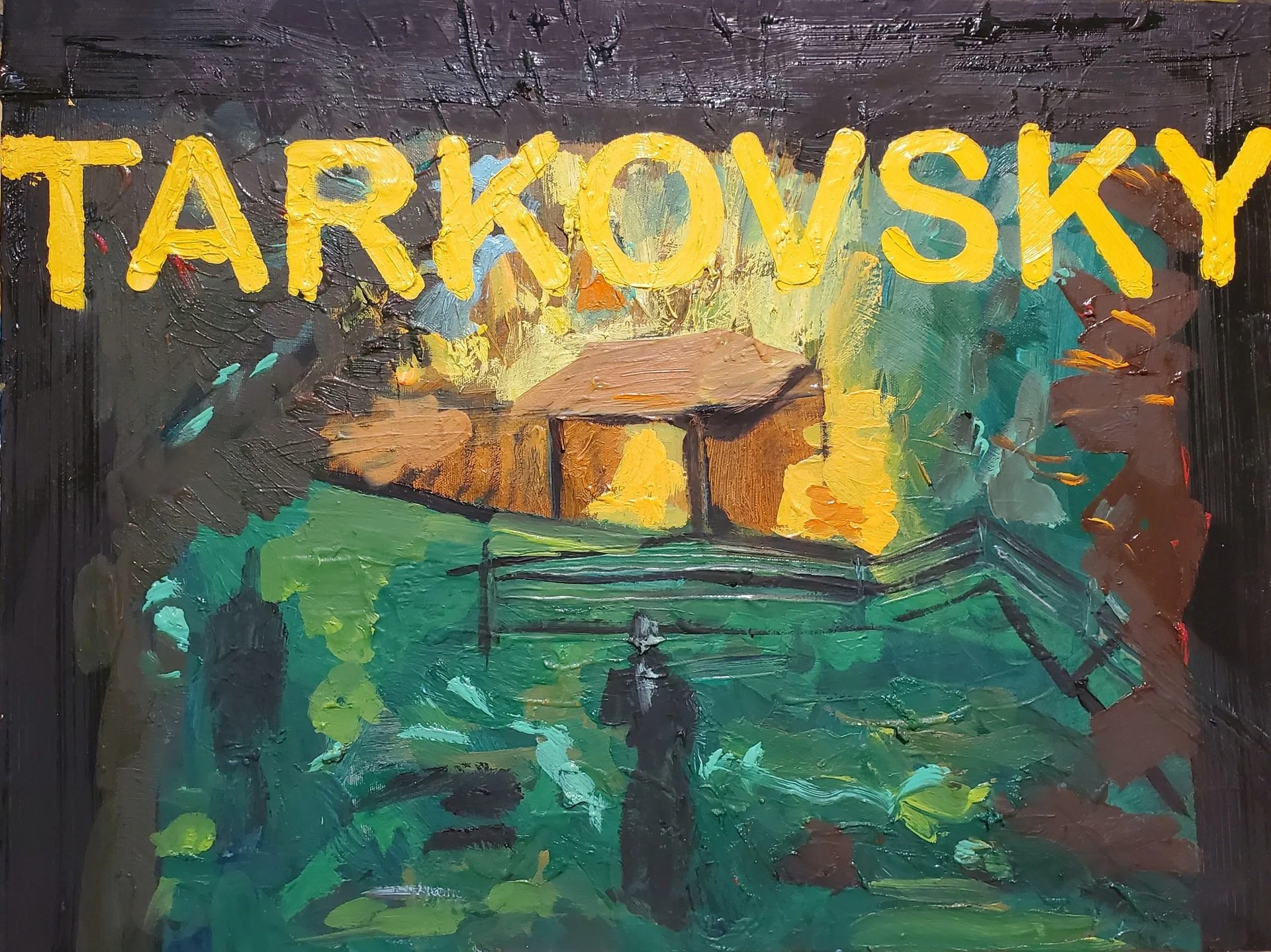

Claudia Doring Baez’s painted film stills of iconic cinematic moments turn the digital into the analog, while Daniel Kingery’s self-portraits are wry appraisals of contemporary culture, interrupting a traditional painted portrait with the black mirror of a smart phone screen, beckoning to lead the protagonist Through the Looking Glass. Geoffrey Stein's portraits of Taylor Swift and Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson are made from New York State Voter Registration Forms and transcripts of Justice Jackson’s confirmation hearing to advocate for civic engagement.

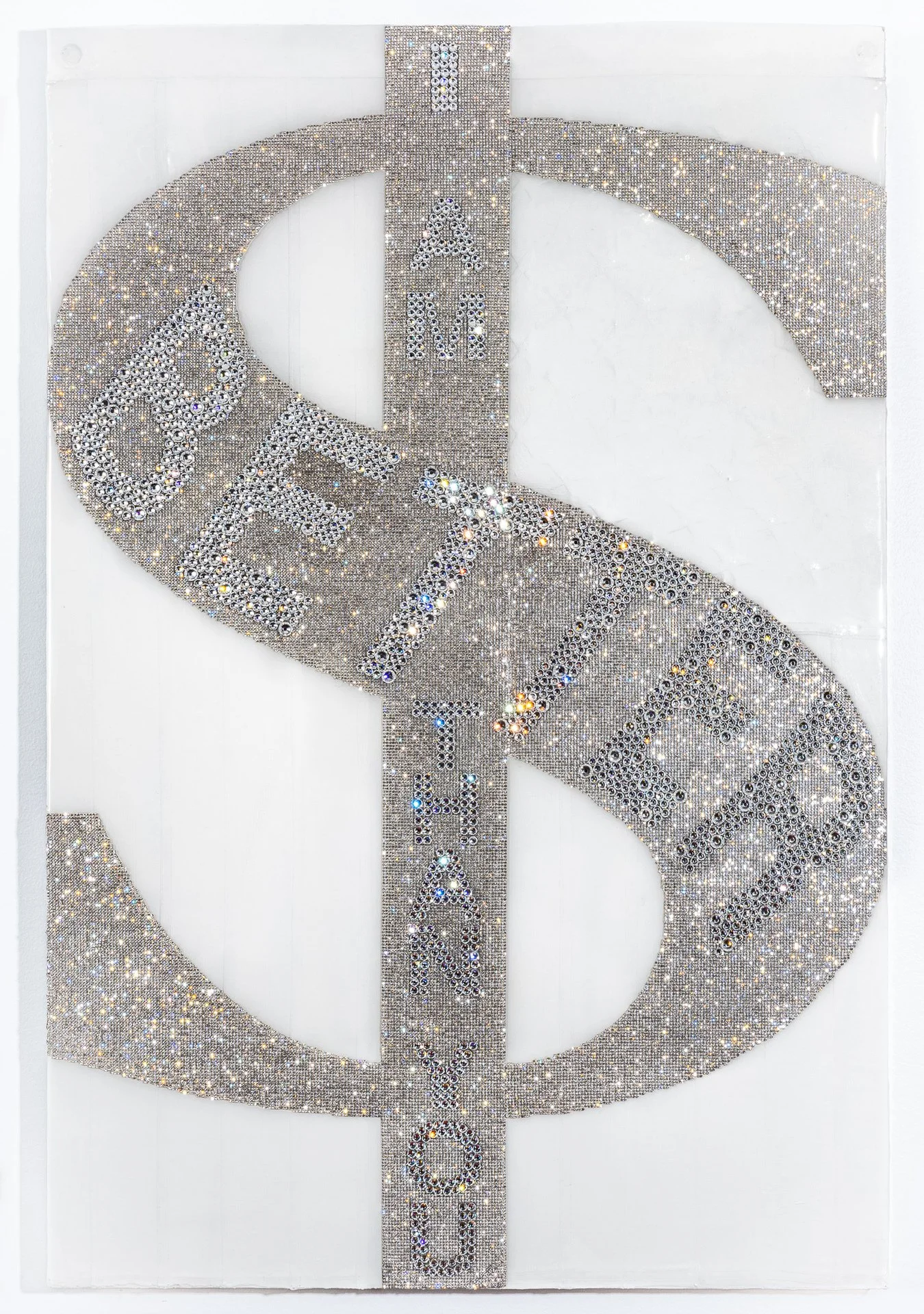

Christos Pantieras’s sculptures take the form of unremarkable changeable letter boards, typically used for frequently changed banal messaging—meeting rooms, menu specials, and arrival times — but here are infused with a weighty humanness, sitting hunched over, tormented by anxiety. Midori Midori uses the instantly recognizable disposable placemat offered at Chinese restaurants as a site for confrontation and reappraisal, replacing zodiac signs with anti-Asian slurs that can not be so easily thrown away. Sol Hill’s pieces utilize the uber recognizable symbols of U.S. currency and patriotism to comment on socioeconomic disparities and an increasing distrust of government.

In Elizabeth Bennett’s postcard Glasshouse, strategically placed tree branches result in a visual joke that also recalls the old expression about people in glasshouses; Michael McNeil’s photograph of a neon sign in a shop window harkens back to Bruce Nauman’s poetic musings on the element.