New Painting

Juried by Rachel Gugelberger

Meanderings: New Painting

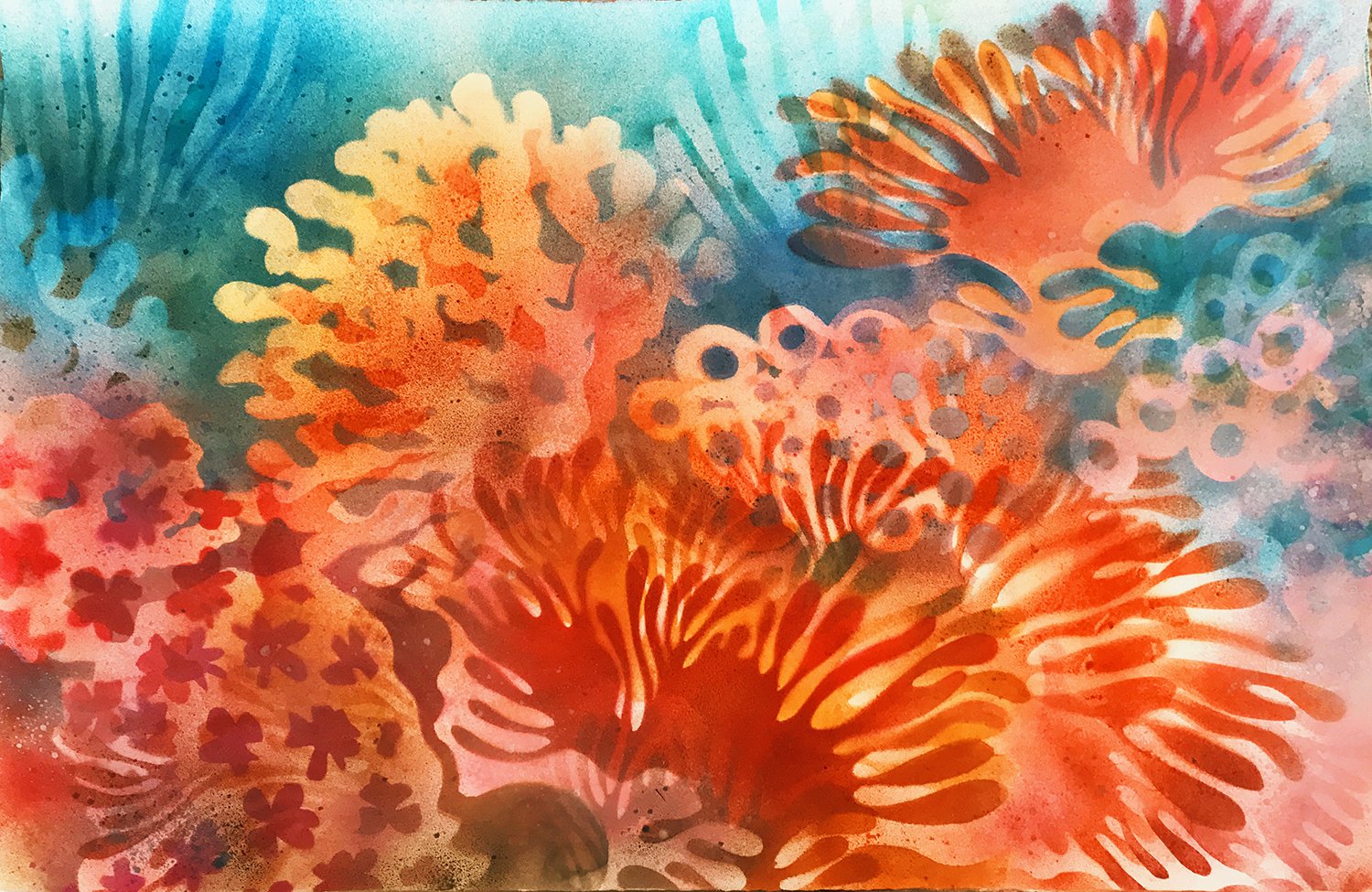

As I write this, the afternoon sun over New York City is attempting to burn through the dense haze caused by record-setting wildfires in Canada, a devastating result of late May heatwaves linked to anthropogenic climate change. With orange-brown smoke coating the sky and the smell of fire in the air, the scene is apocalyptic. The thick cloud barrier offered a rare occasion to get a decent photograph of that notoriously difficult subject, the Sun. As people looked skyward, it was a moment to pause on the many painterly representations of the Sun. From Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise, showing the Sun casting an orange glow across the post at Le Havre through a misty haze in the late 19th century, to Frida Kahlo’s Sun and Life (1947), which fixes on a mesmerizingly blood-red, three-eyed sun, surrounded by the plants nourished by her live-giving light, the Sun has fueled painting for generations.

In light of this moment, I find myself gravitating toward works that—through a host of divergent approaches and strategies—stretch the possibilities of painting in subtle and sometimes surprising ways. Experiments in form and material abound, eliciting a sensorial and emotional reference to the world.

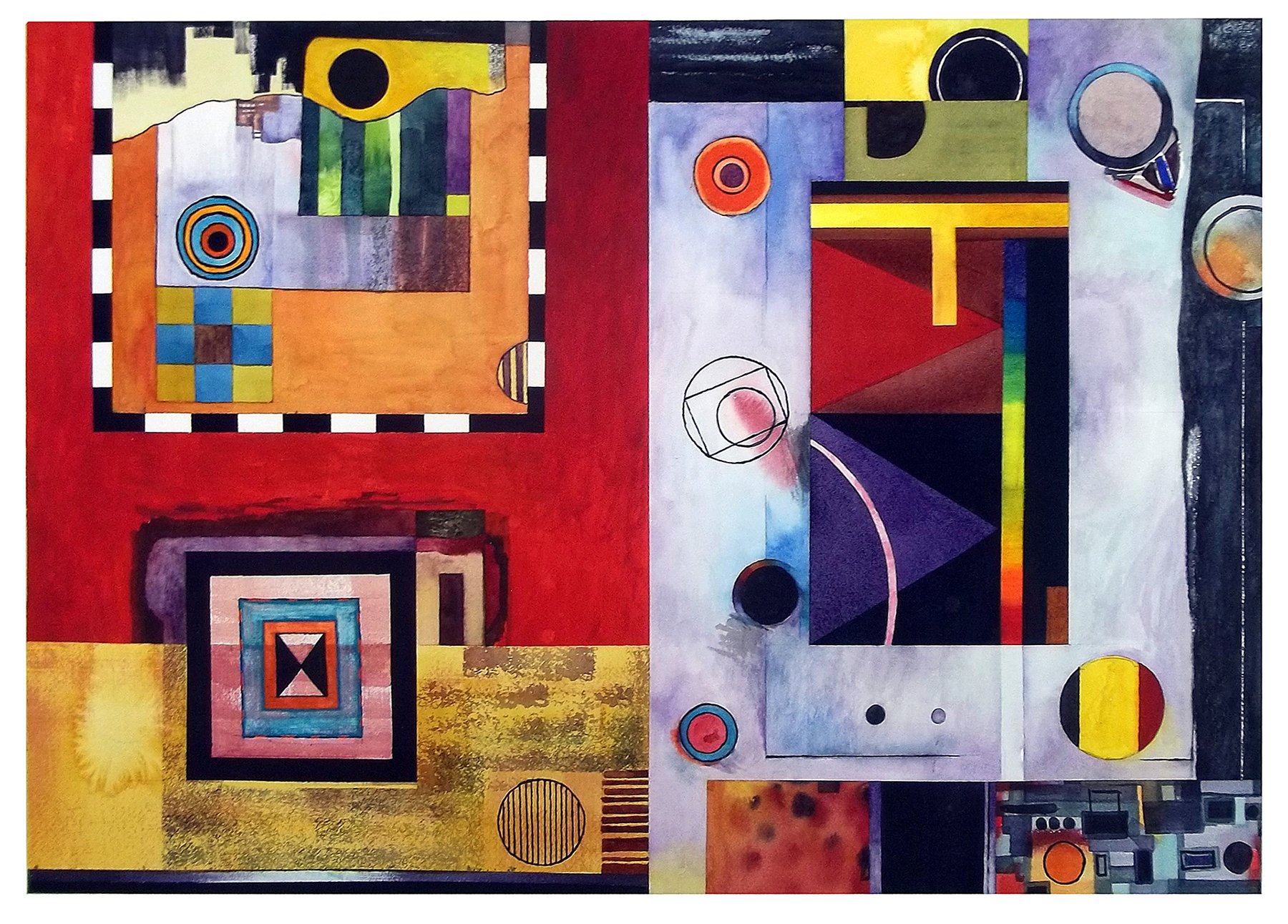

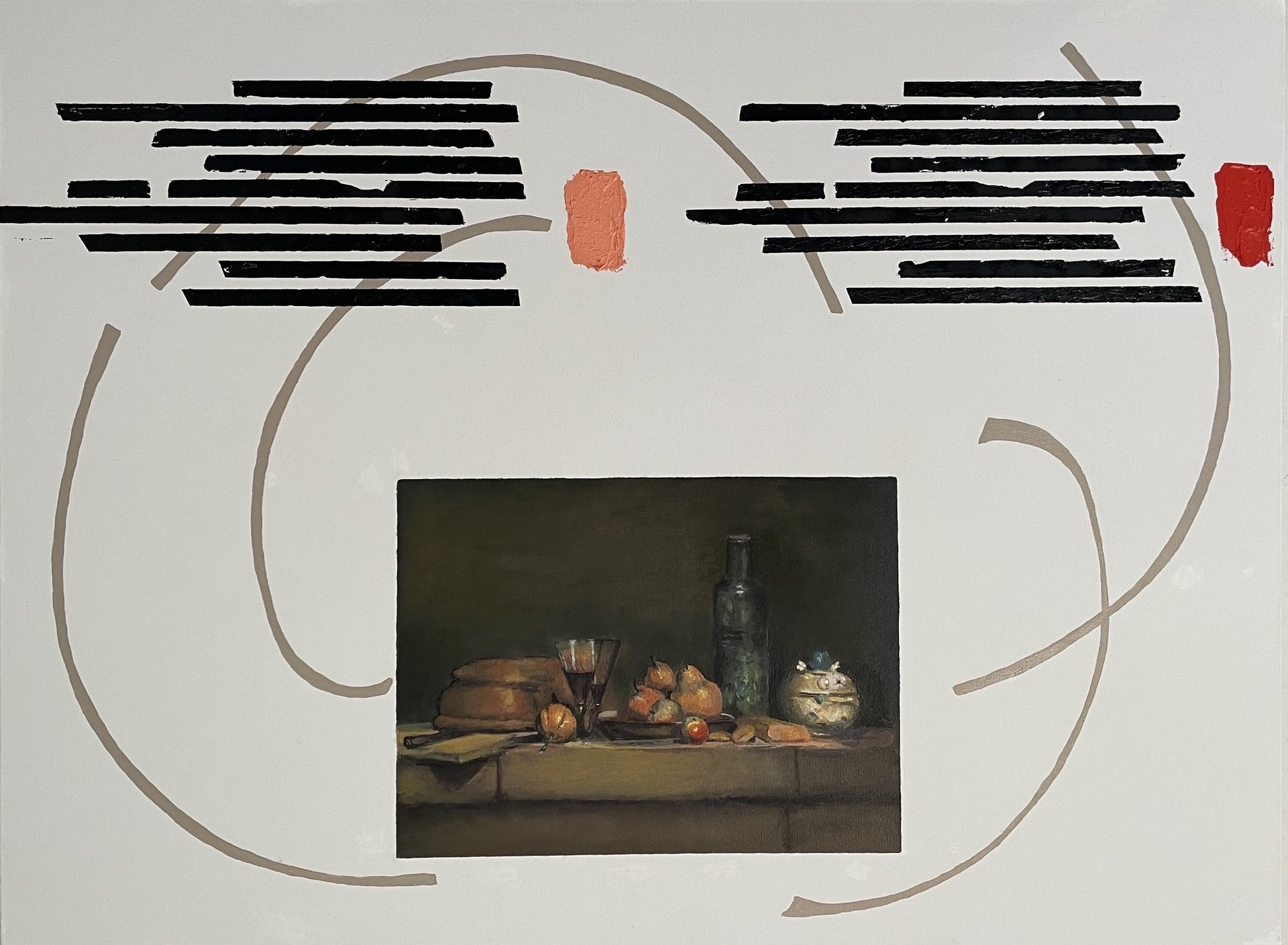

Of course, the invitation to curate an online exhibition of works submitted to a call for “New Painting” suggests that there is such a thing as “old painting.” And it is with this prompt (taking “old” to mean “traditional”—not “painted a long time ago”) that I approached the selection, leaning into works that challenged characteristics of traditional painting; creating a sort of “community of paintings” in which defamiliarization, emotion, and social commentary collide and converse. (And if not evident by the eye alone, meaning was conjured with a little bit of help from the title.)

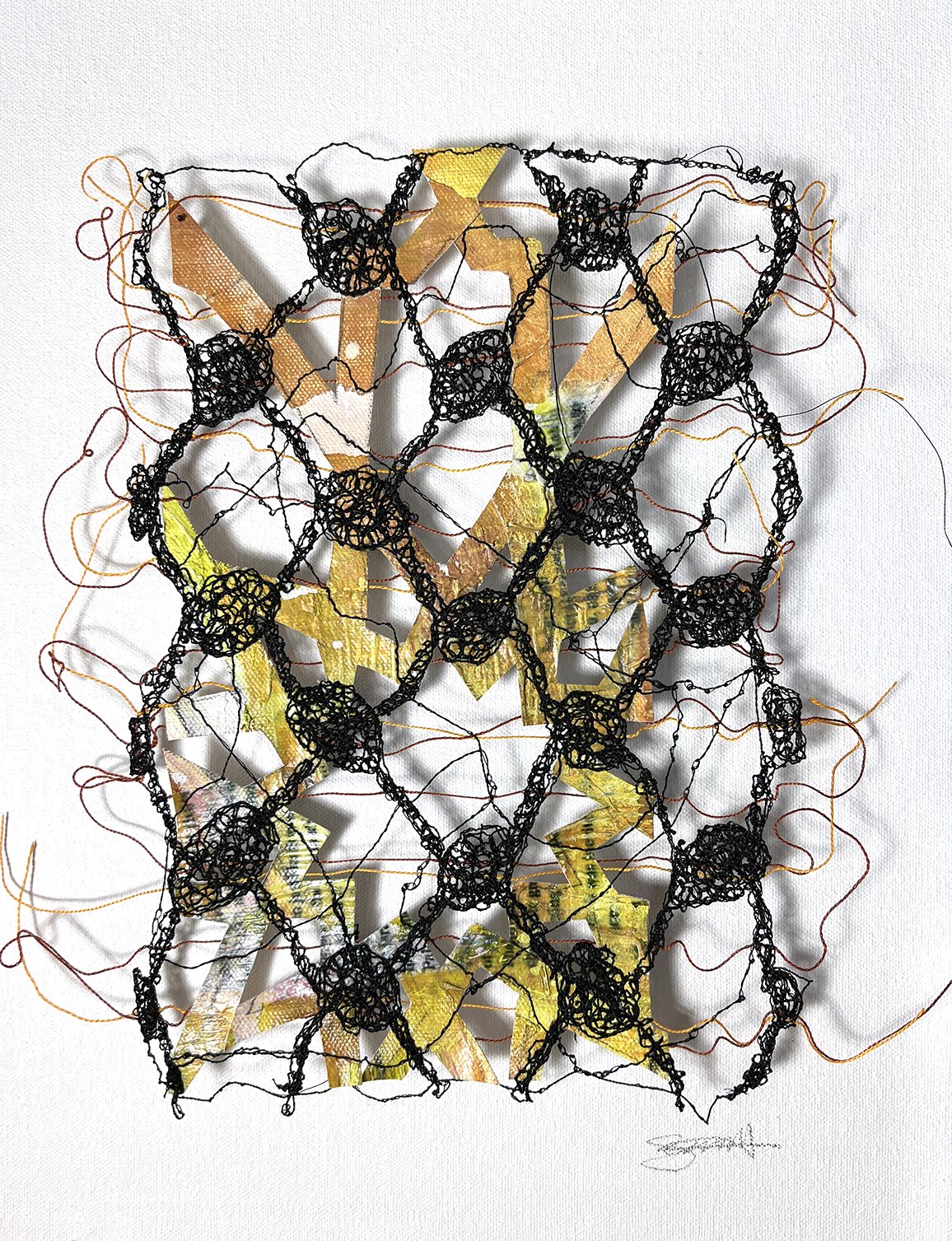

Since the French historical painter Paul Delaroche first laid eyes on a daguerreotype in 1839 and proclaimed that painting is dead, interlopers (photography, drawing) have arrived to carry its standard, cast as “the new painting.” It was just days ago that ArtNews declared that “fiber is the new painting.”

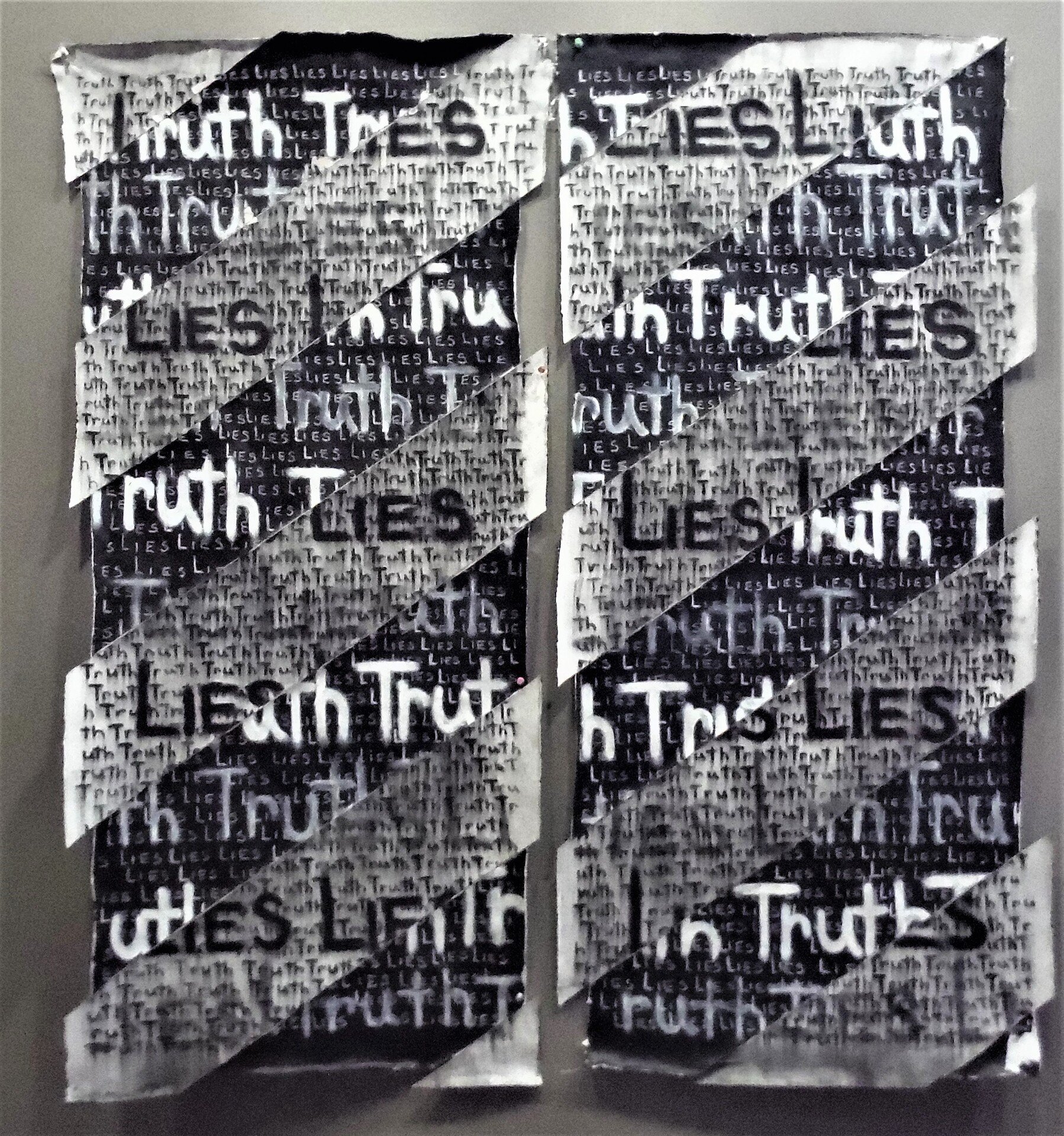

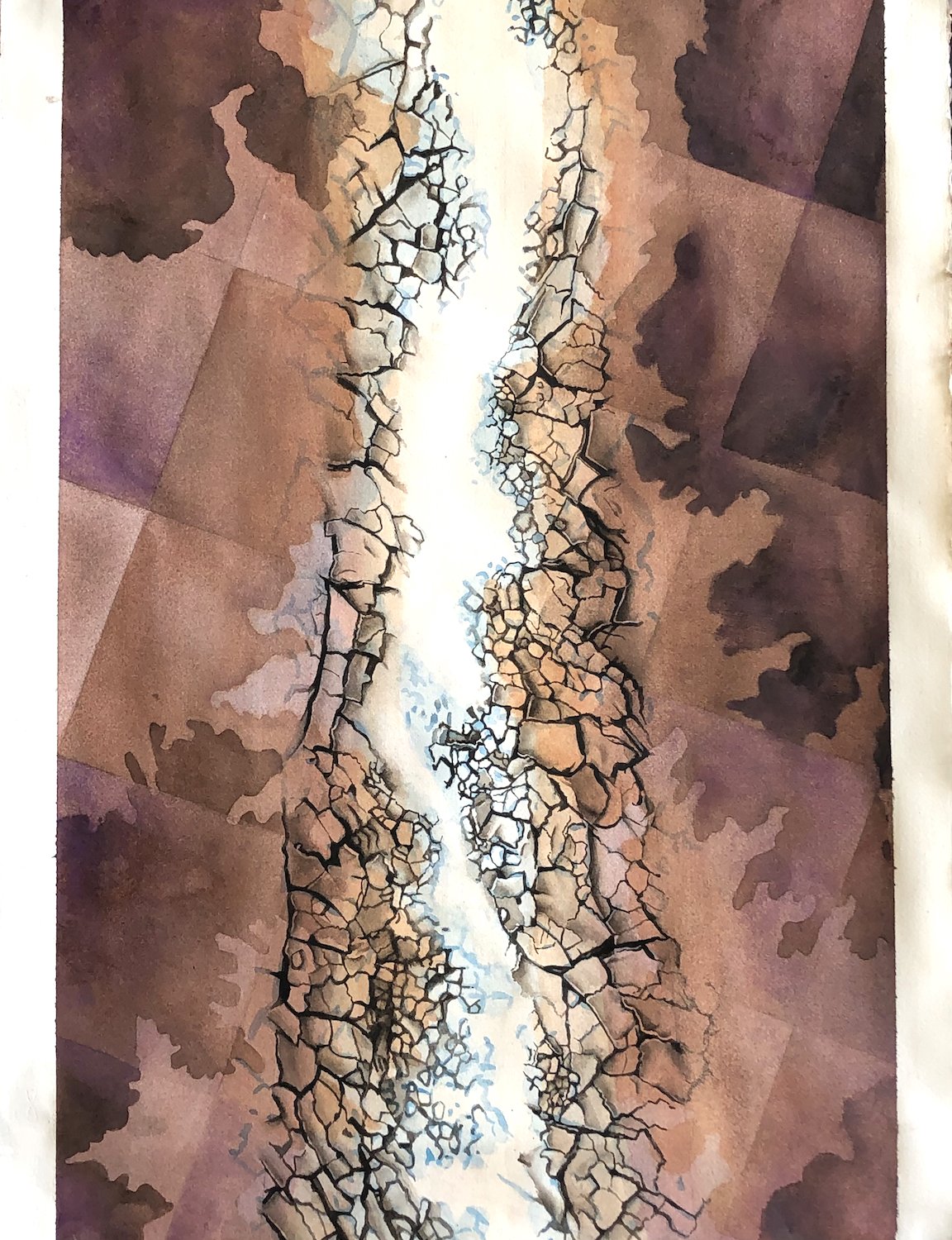

Painting—that is, when an artist applies “paint” or another medium to a surface— continues to evolve with the growing creativity of new generations of artists and advancing technology introduces new materials. But there is also the subject matter of painting—where culture, politics and society come into play. We are living in unprecedented times: Powerful uprisings demanding racial, gender and environmental justice, reckonings with our nation’s dark history, the COVID-19 pandemic and the climate crisis. Natural detail through the lens of romanticism has long receded from the canvas, usurped by the dystopian, capturing the chaos of the mind and the anxiety of humanity. Perhaps anxiety is the defining spirit, mood, or ethos of “new painting”—and with it a rejection of living, creating, depicting, and naming according to old structures.

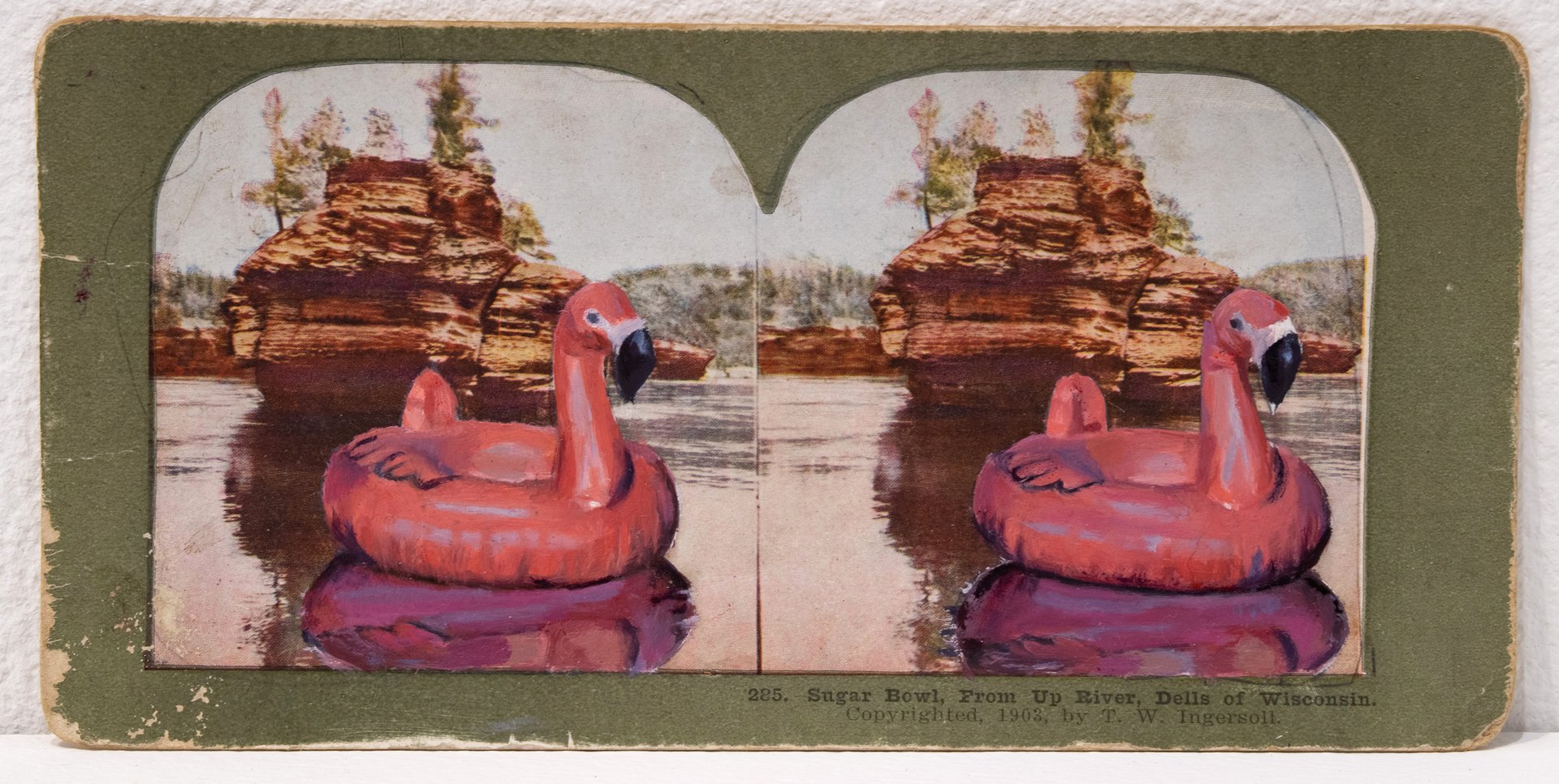

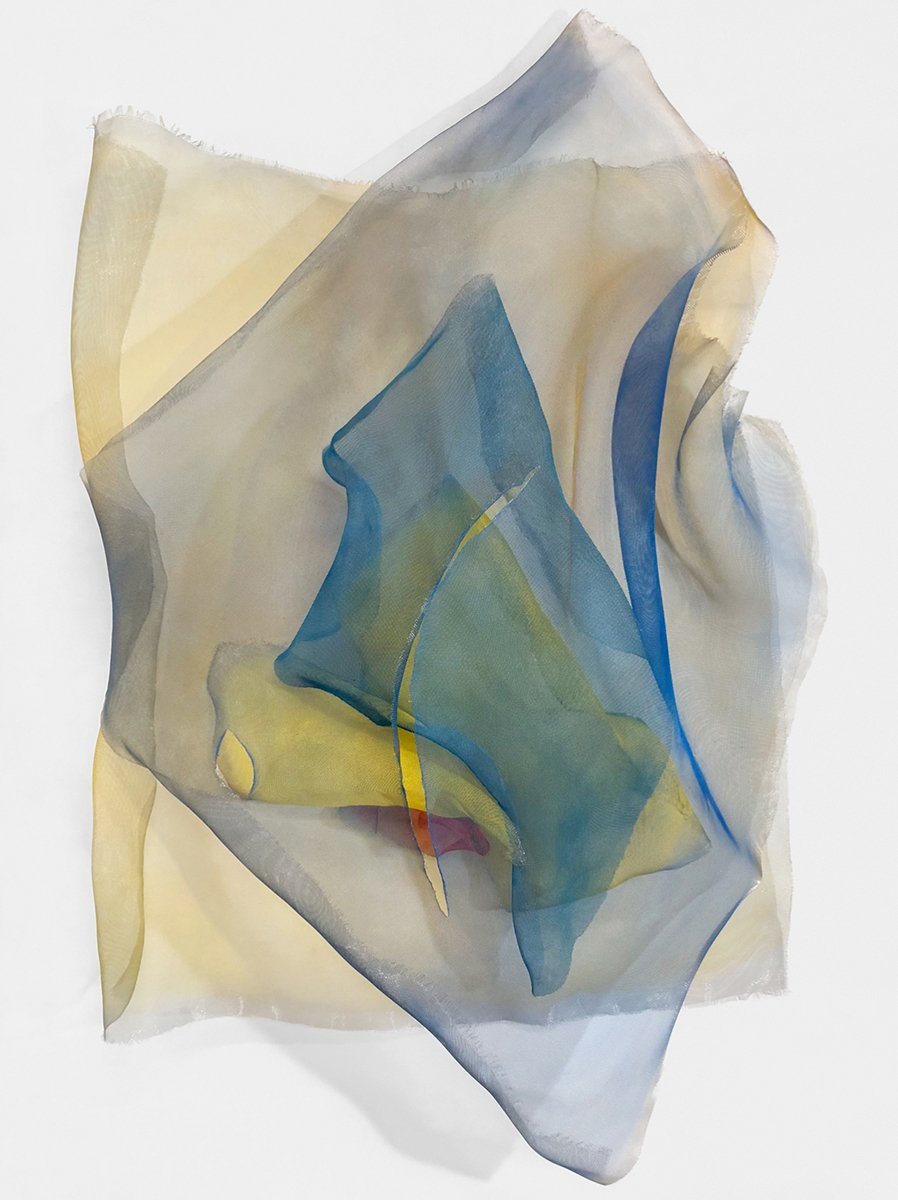

The word painting comes from the Latin “pingere,” which means to mark, or to stain, which implies affixing something (like, traditionally, paint, or more recently, fabric, yarn, or other materials or objects) onto a substrate. But pingere is also etymologically related to “spingere,” which means to push, press, drive, or even lead. Perhaps it is this more archaic meaning that the artists here demonstrate. For these artists, it is, of course, about making marks. But looked at together, perhaps it is also about pushing an entire medium. Ranging from abstraction and the defamiliarization of the everyday to material and referential responses to the chaos (and absurdity) of our current moment, the meaningful differences between real/fiction, recognizable/imperceptible, and remembered/imagined collapse here into a matter of perception.

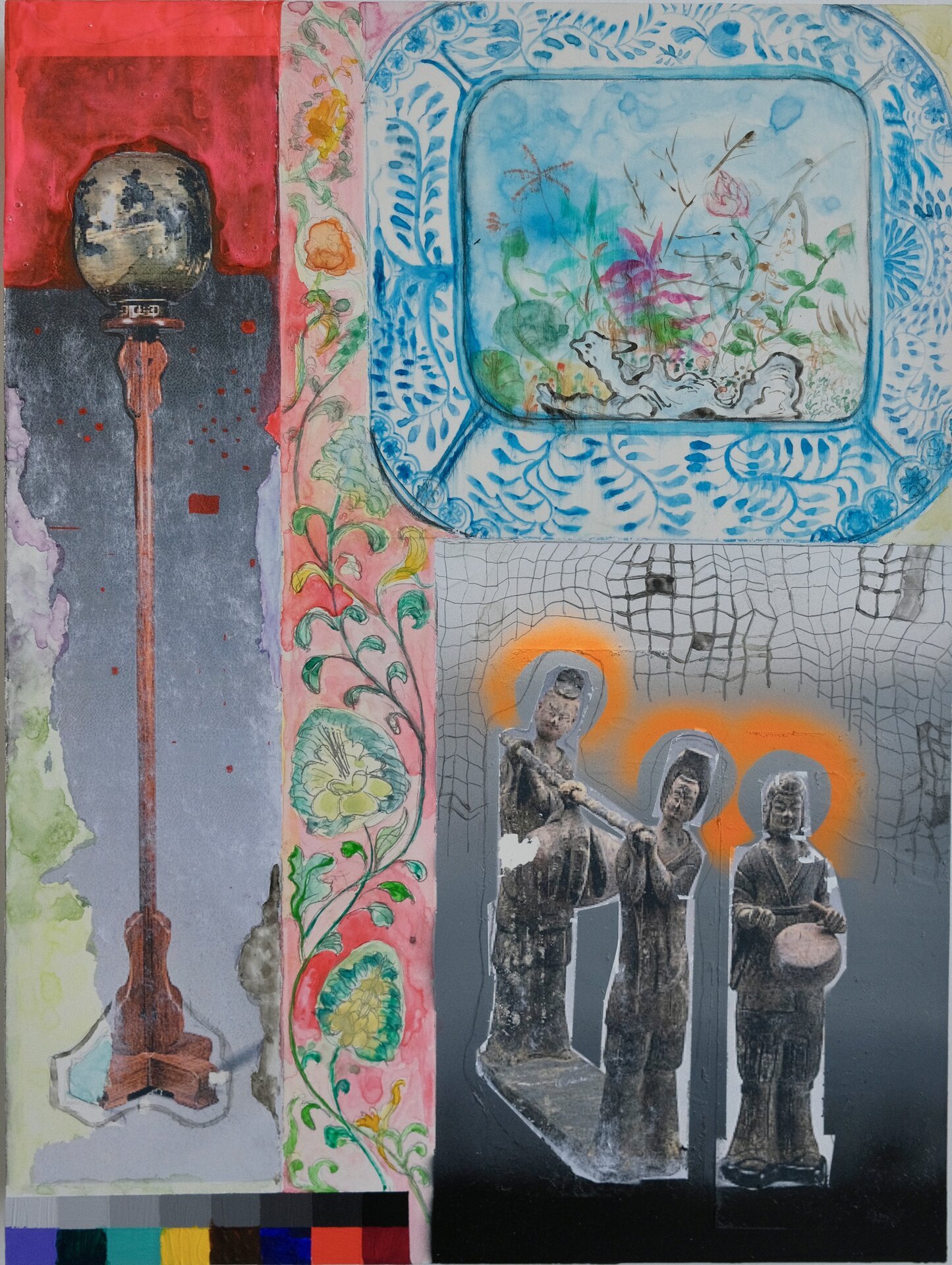

Wall 1

Employing a range of materials and in a variety of styles; text-based works, collage, figurative, conceptual and seemingly abstract and formal compositions touch on temporal, environmental, cultural and sociopolitical themes that are rooted in the past and projected into the future

Wall 2

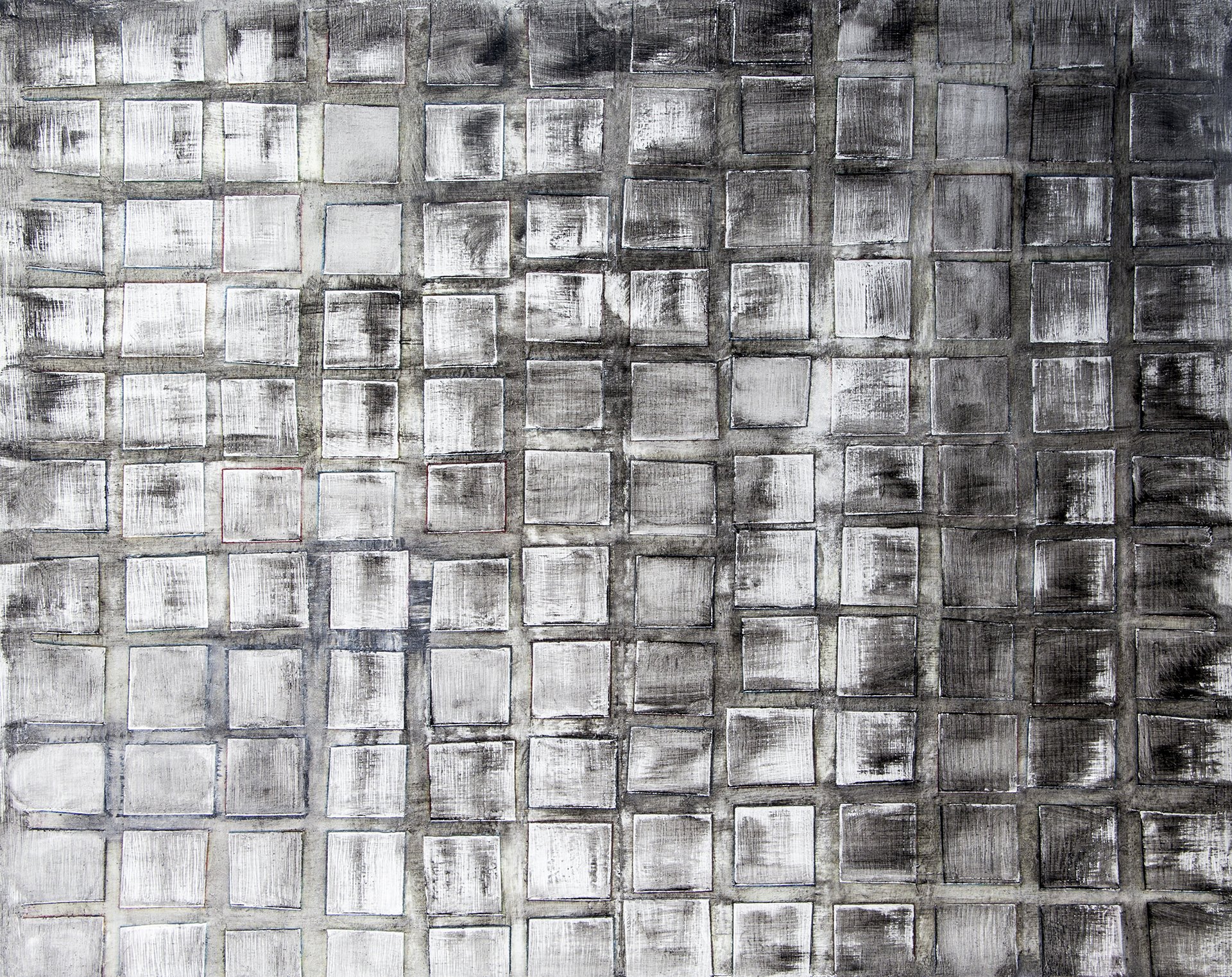

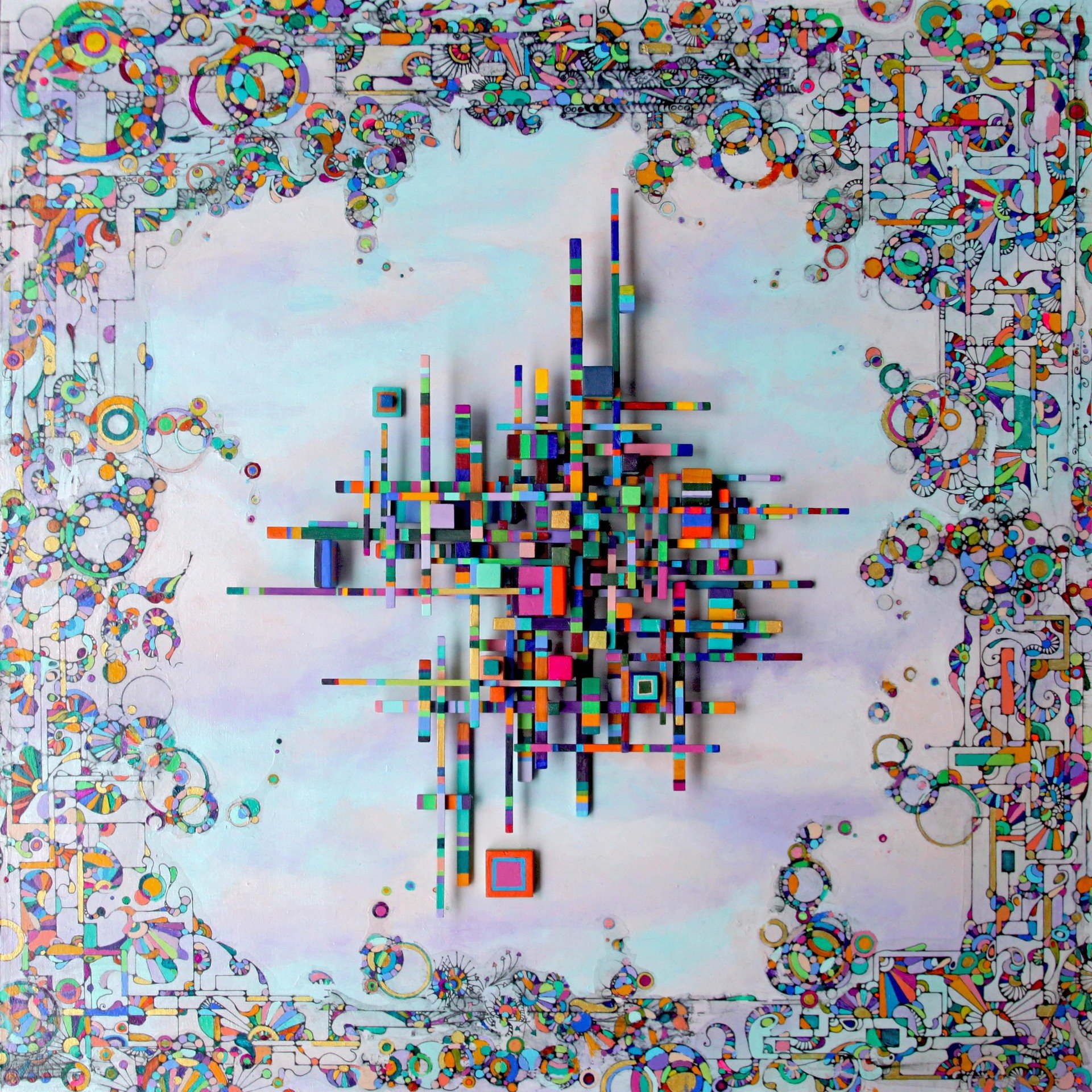

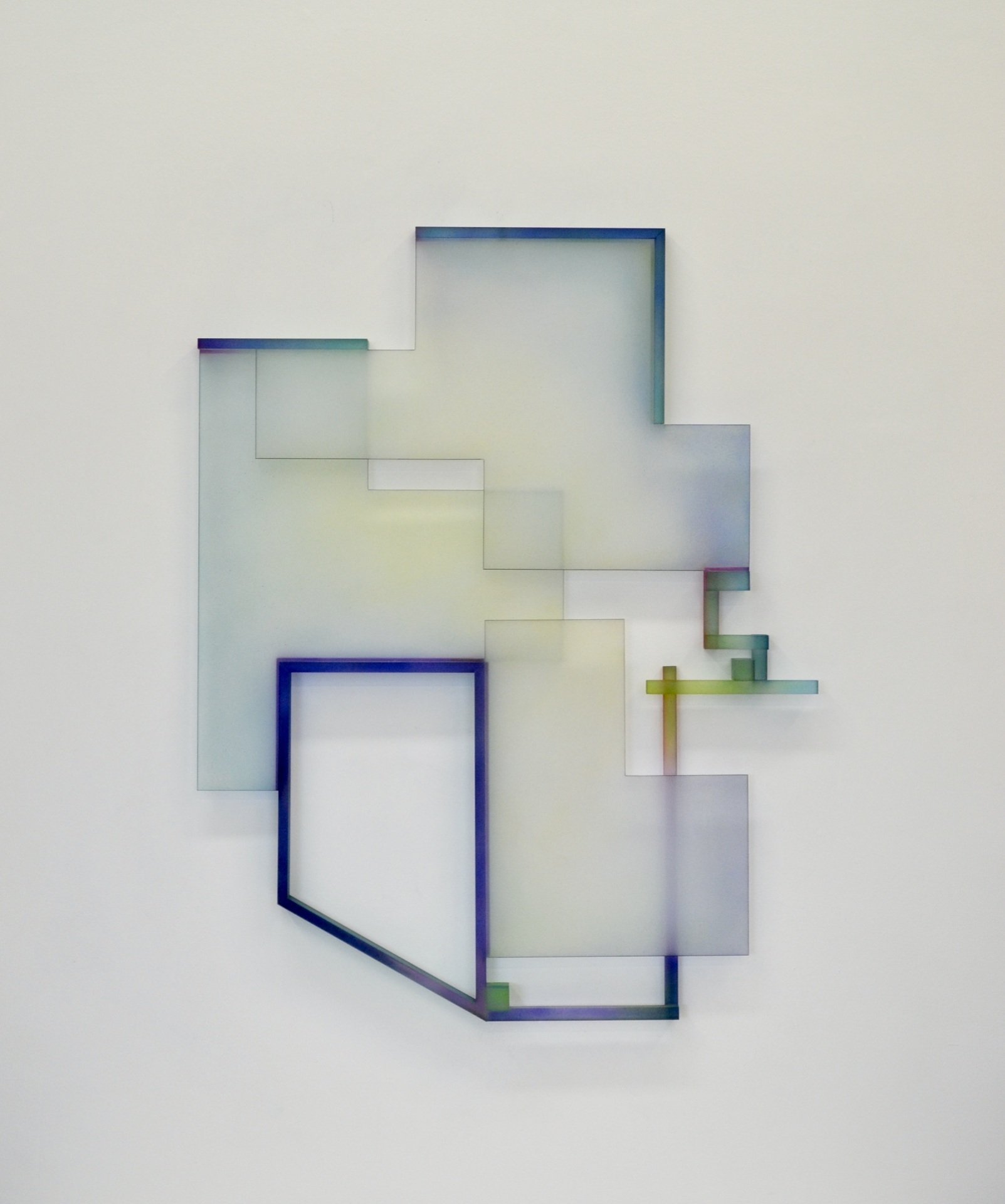

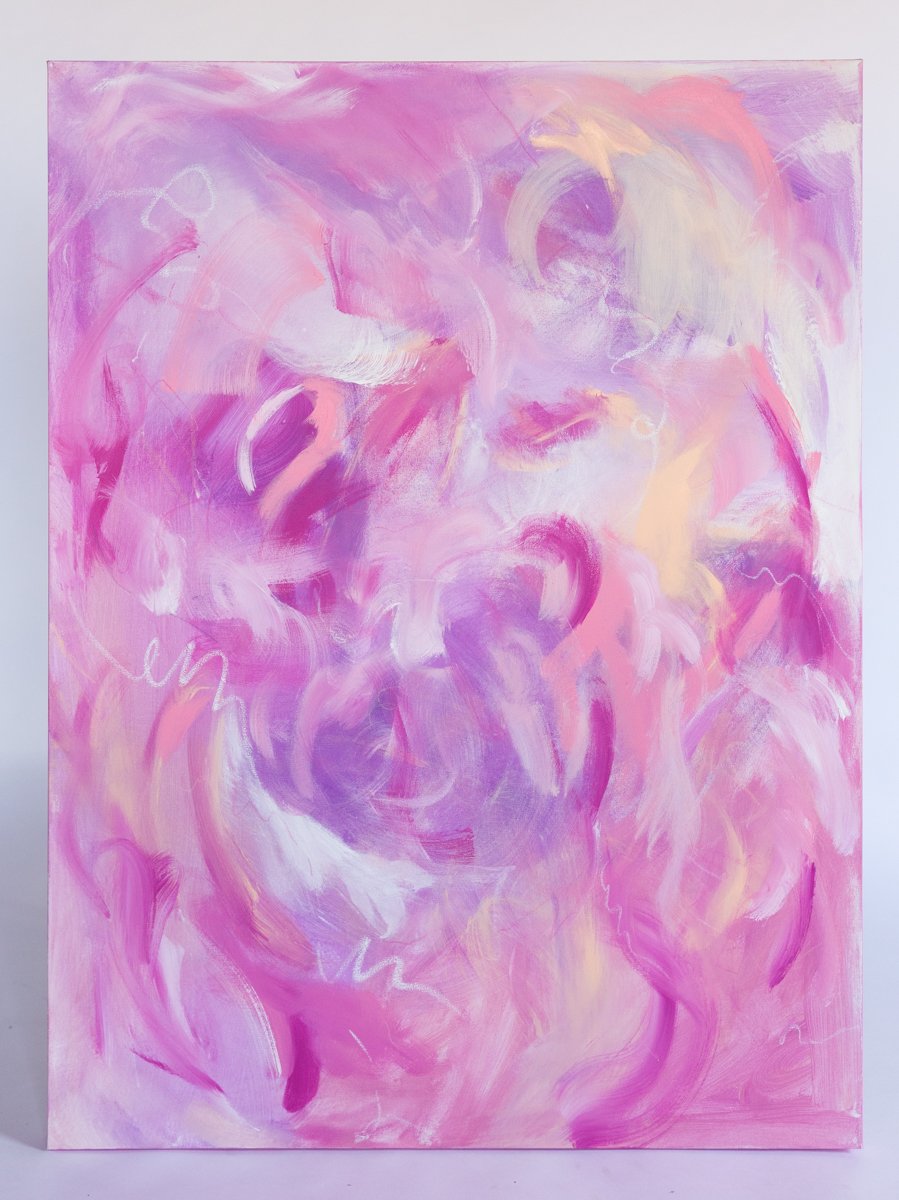

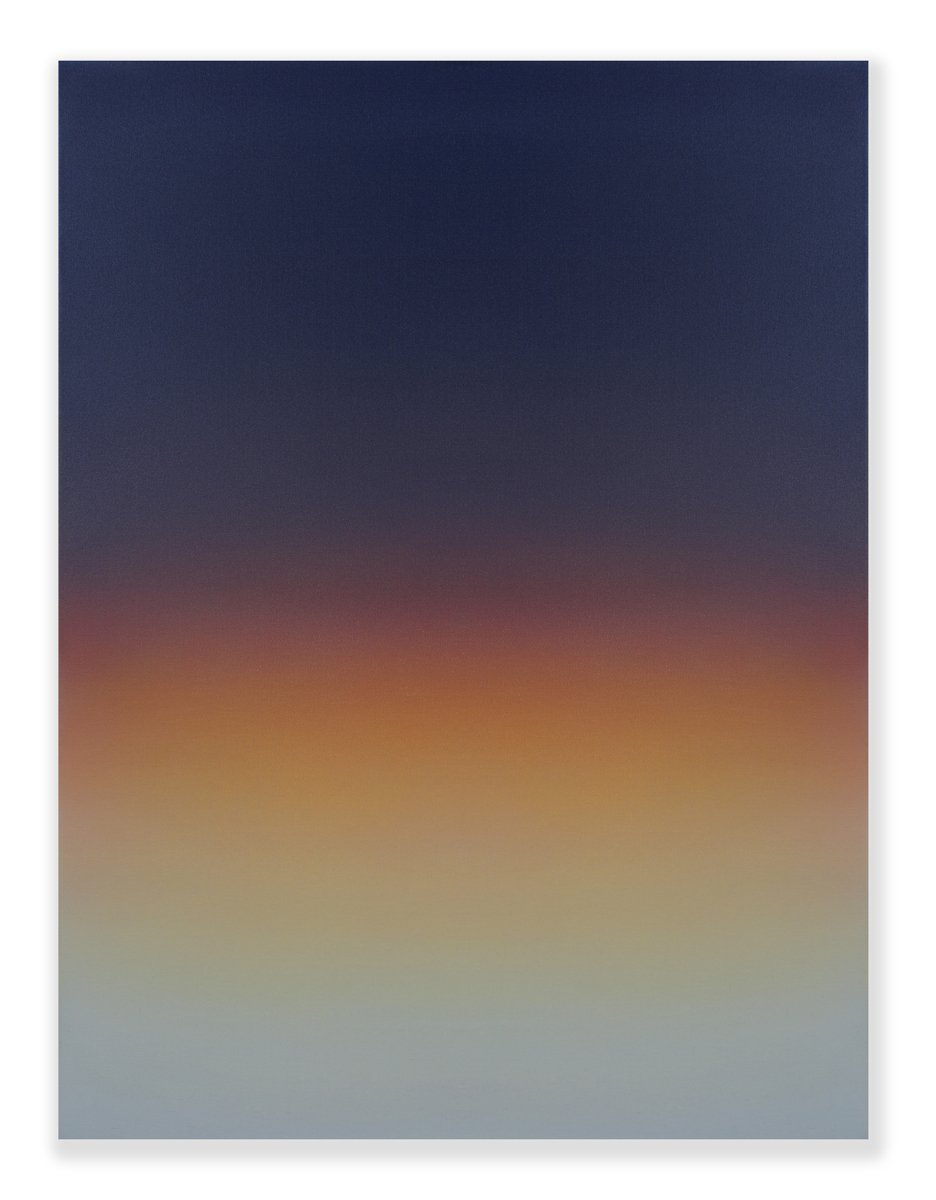

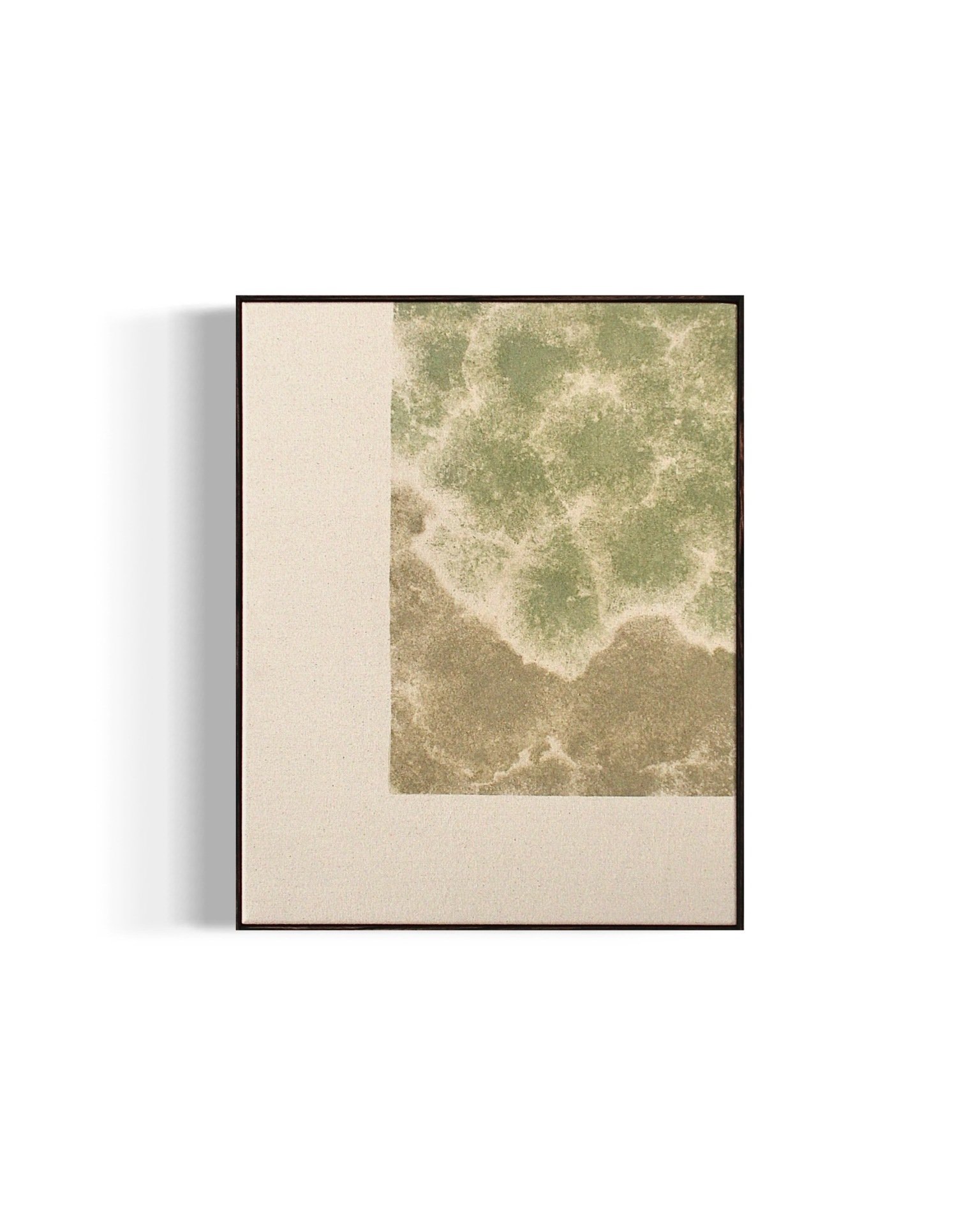

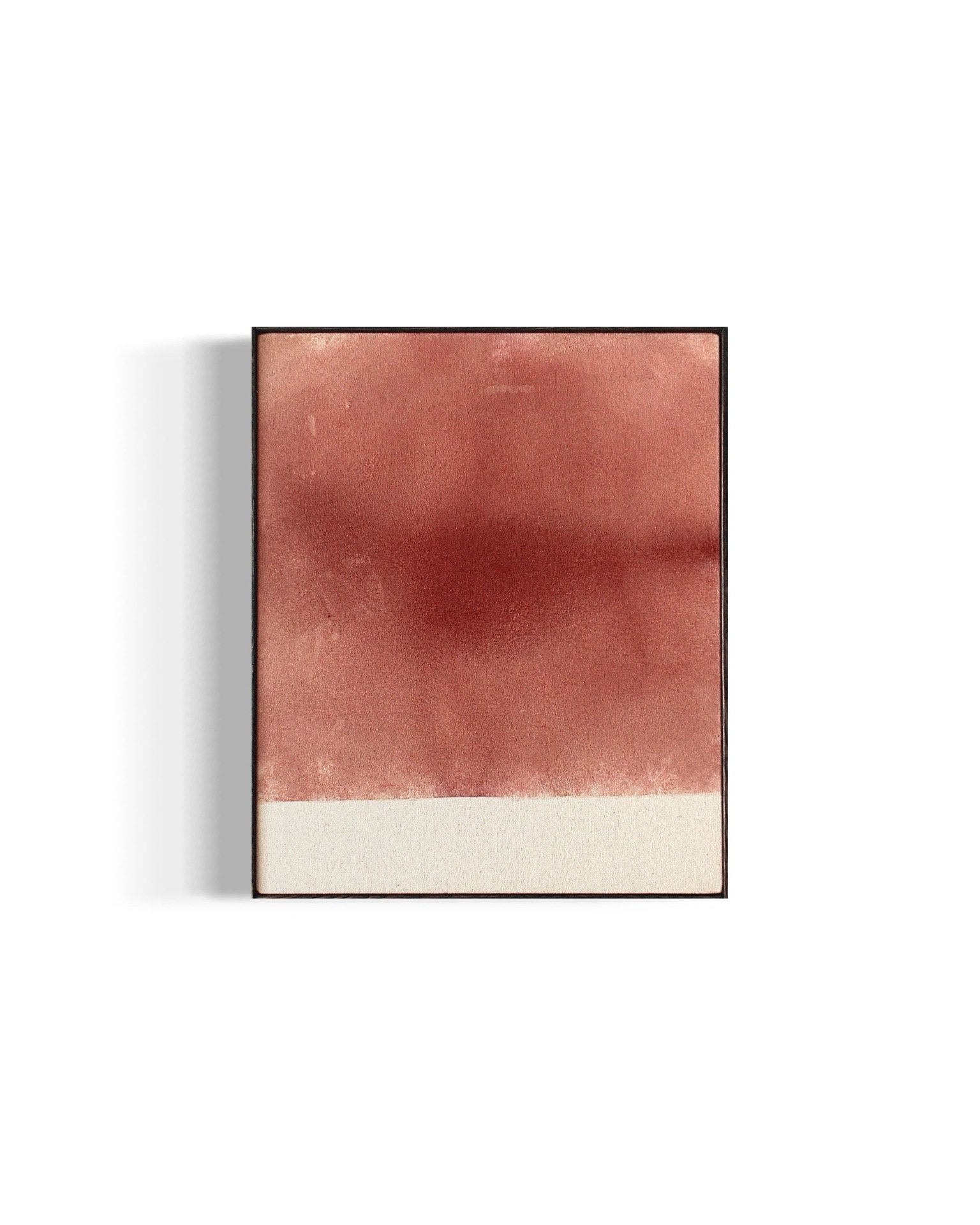

Ceramics, feathers, rubber, yoga matting, 3d-printed crumpled paper bags and even condensed ambient air are just a few of the most “unconventional” materials that challenge painting. Thread is used to create color field compositions and back-lit paper to capture seasonal moods. A glyph-shaped canvas nods to modernist literature, abstract brushstrokes suggest autumn’s flush (or is it wildfires?) and Barbie’s pink wardrobe inspires gestural color painting. Context may be decontextualized but finding connections/associations with the lived world is irresistible: in a repetition of grids I think of quilts, a matrix, see a street block or an aerial view of farmland. Emphasizing compositional elements, unconventional materials, sewing and craft techniques, time and labor, the painterly works here are liberated from the constraints of art history and suffer nonetheless for their entanglements with the painterly.

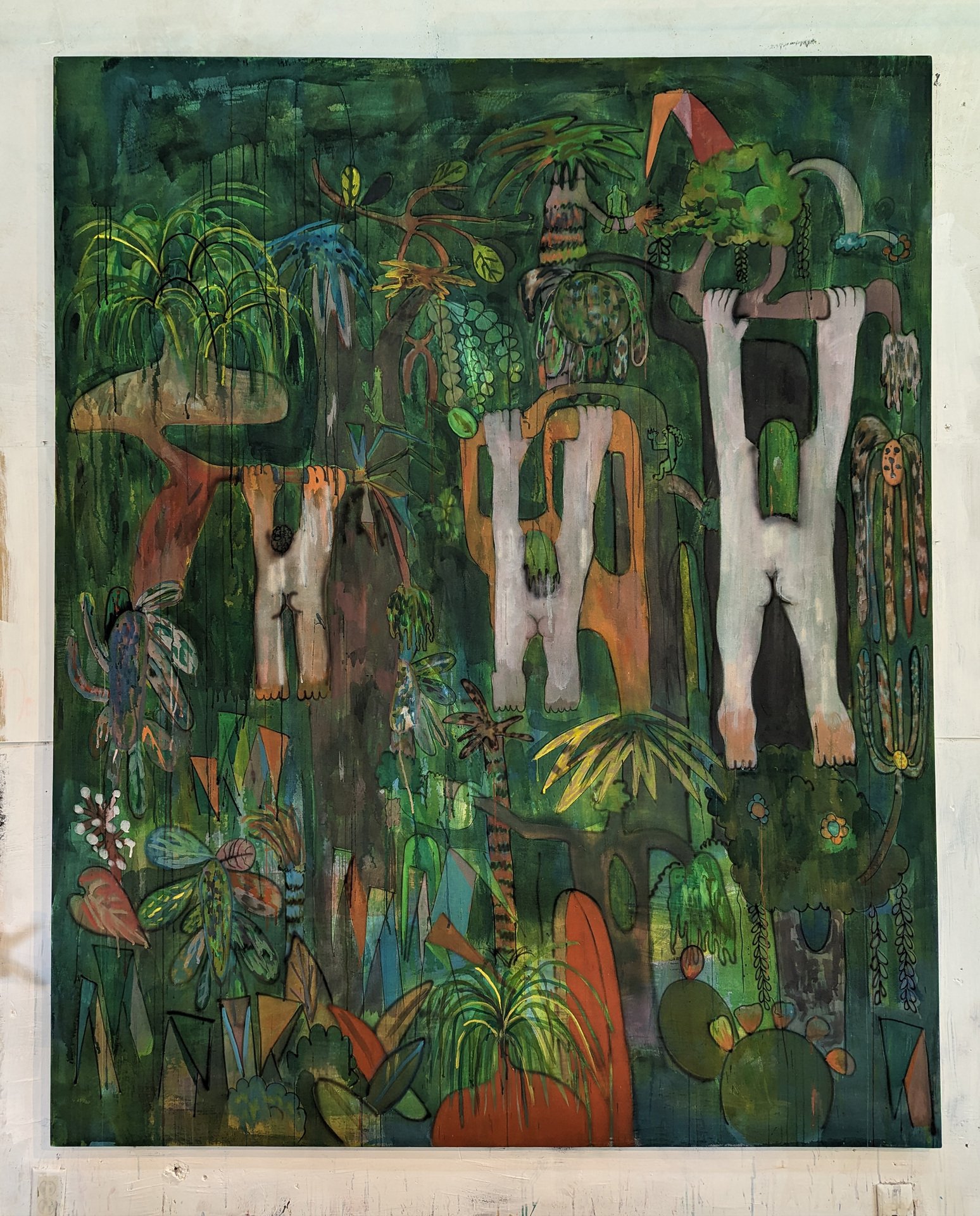

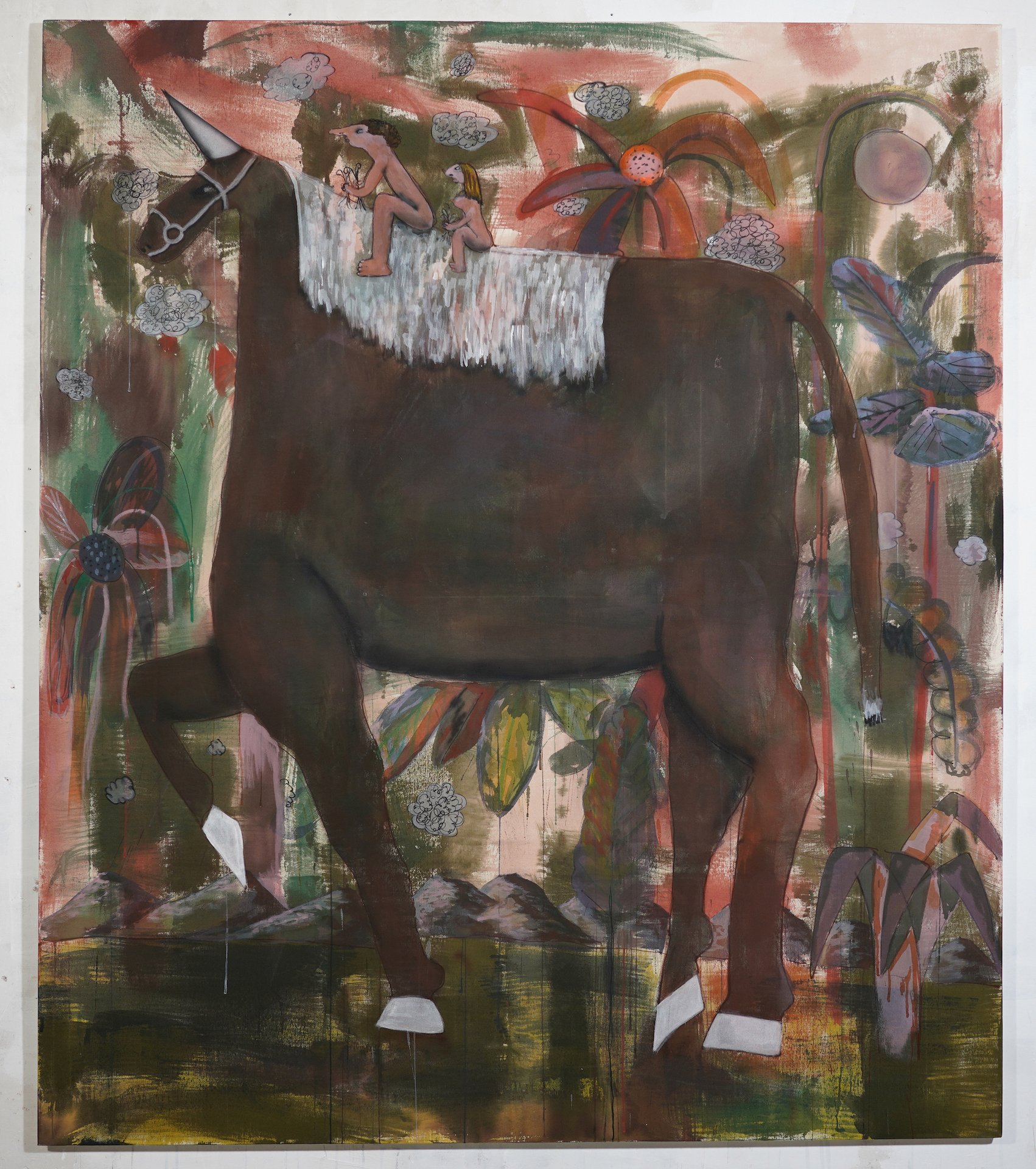

Wall 3

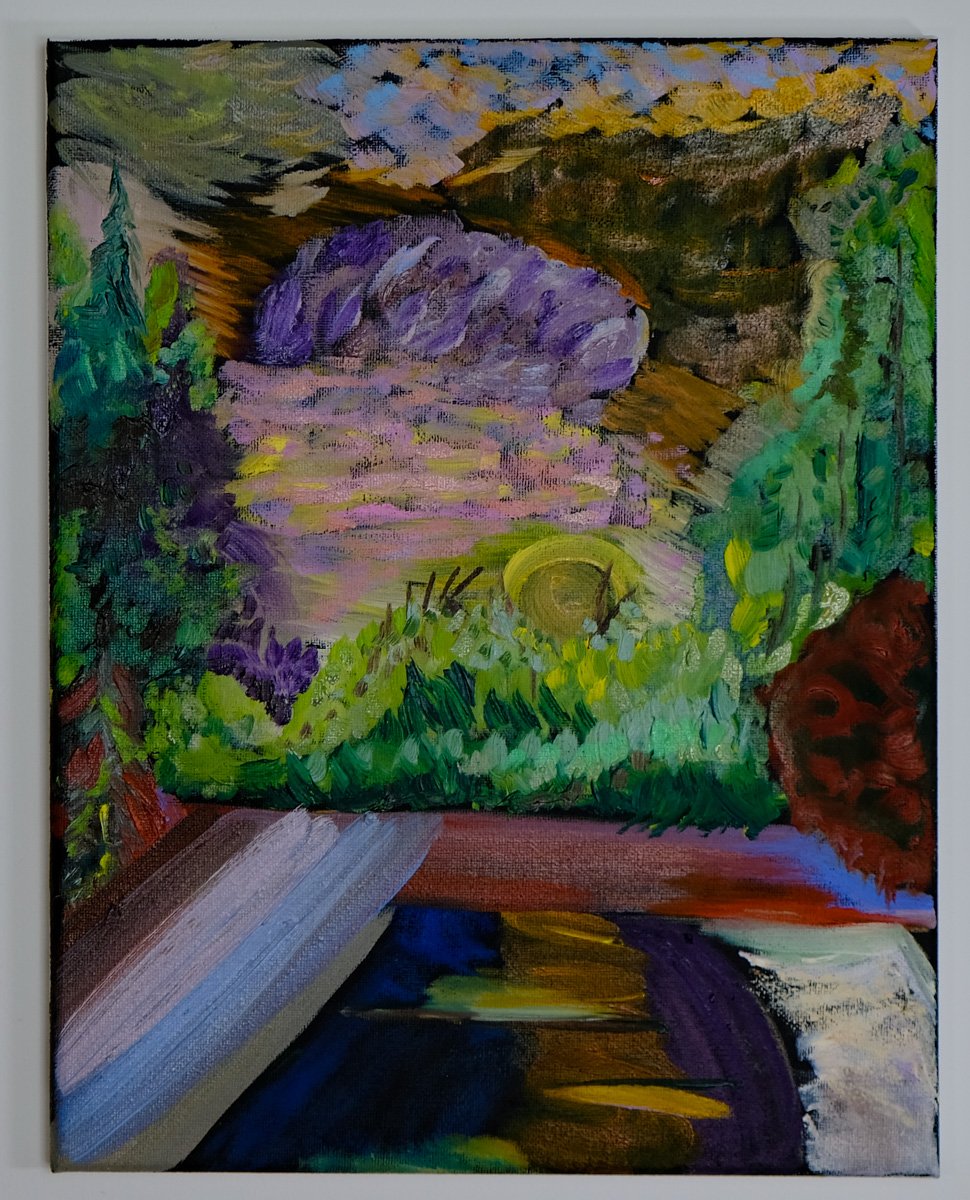

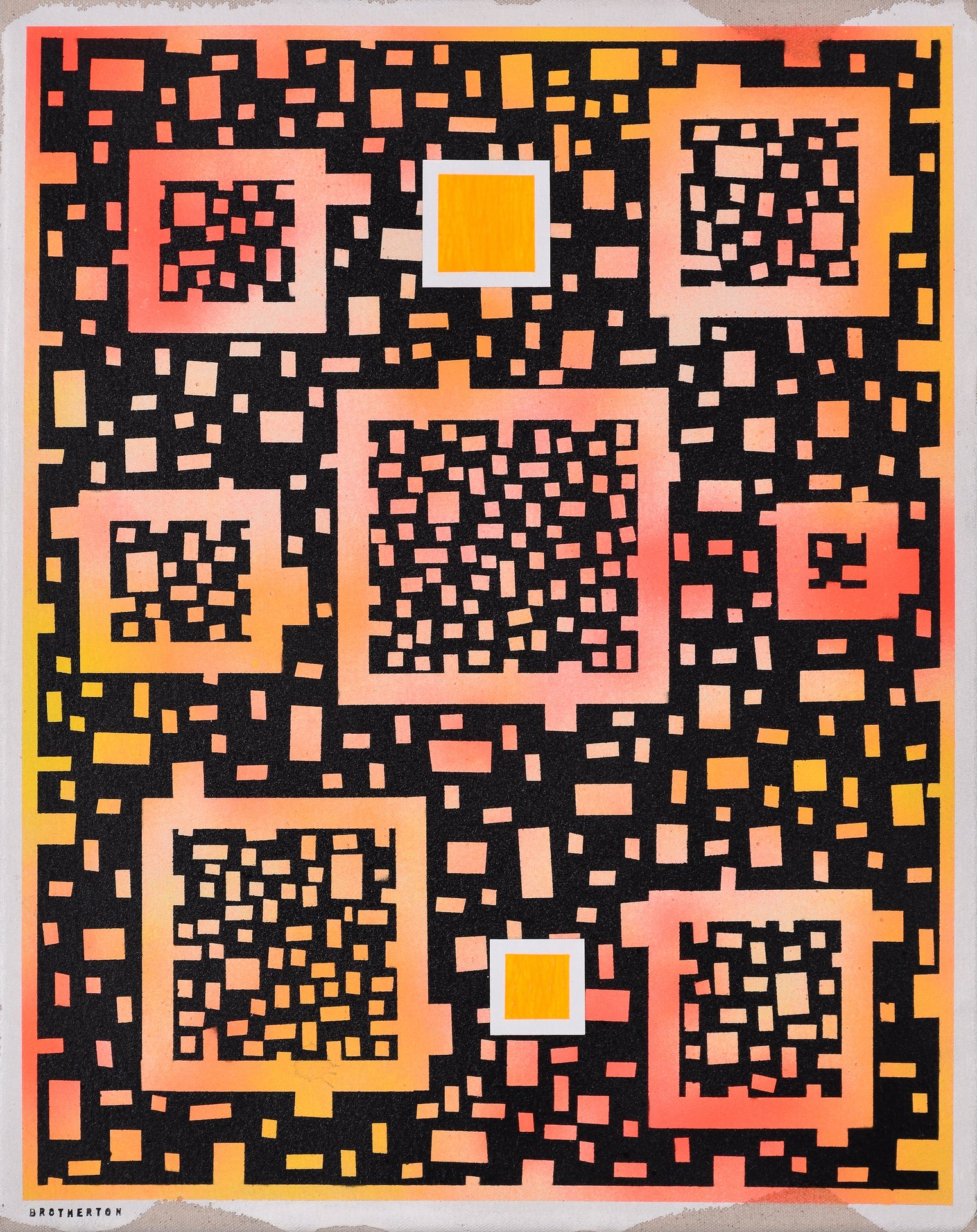

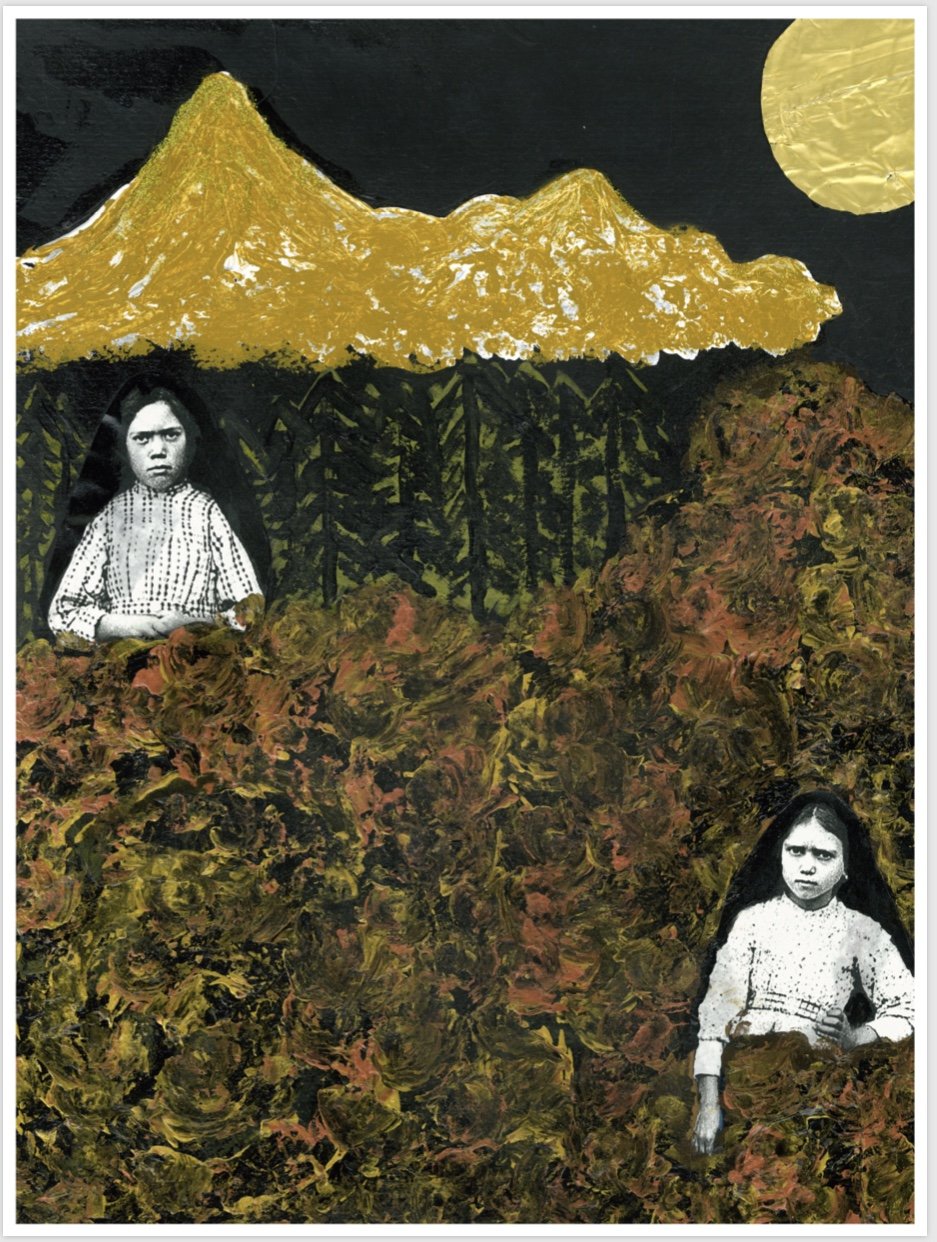

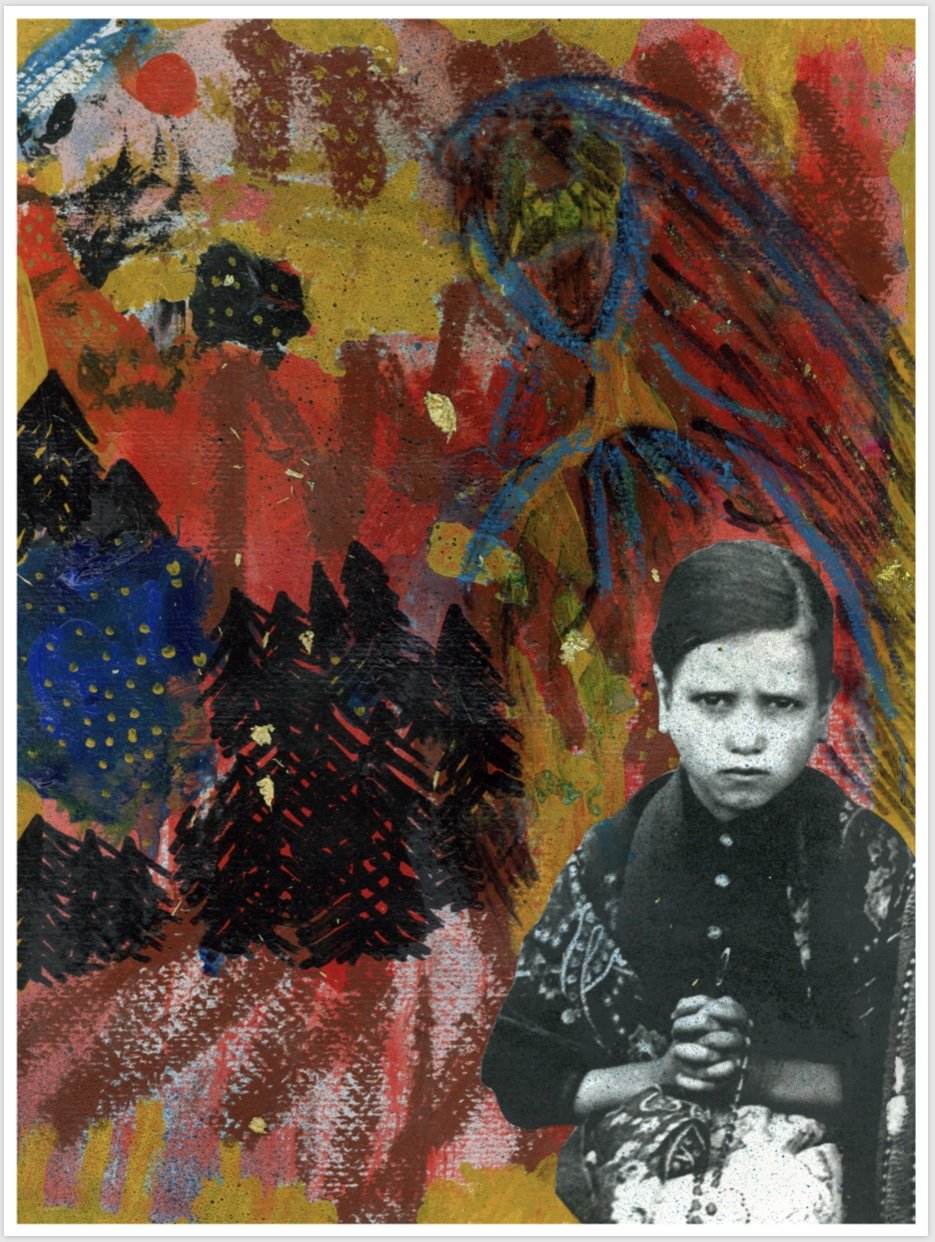

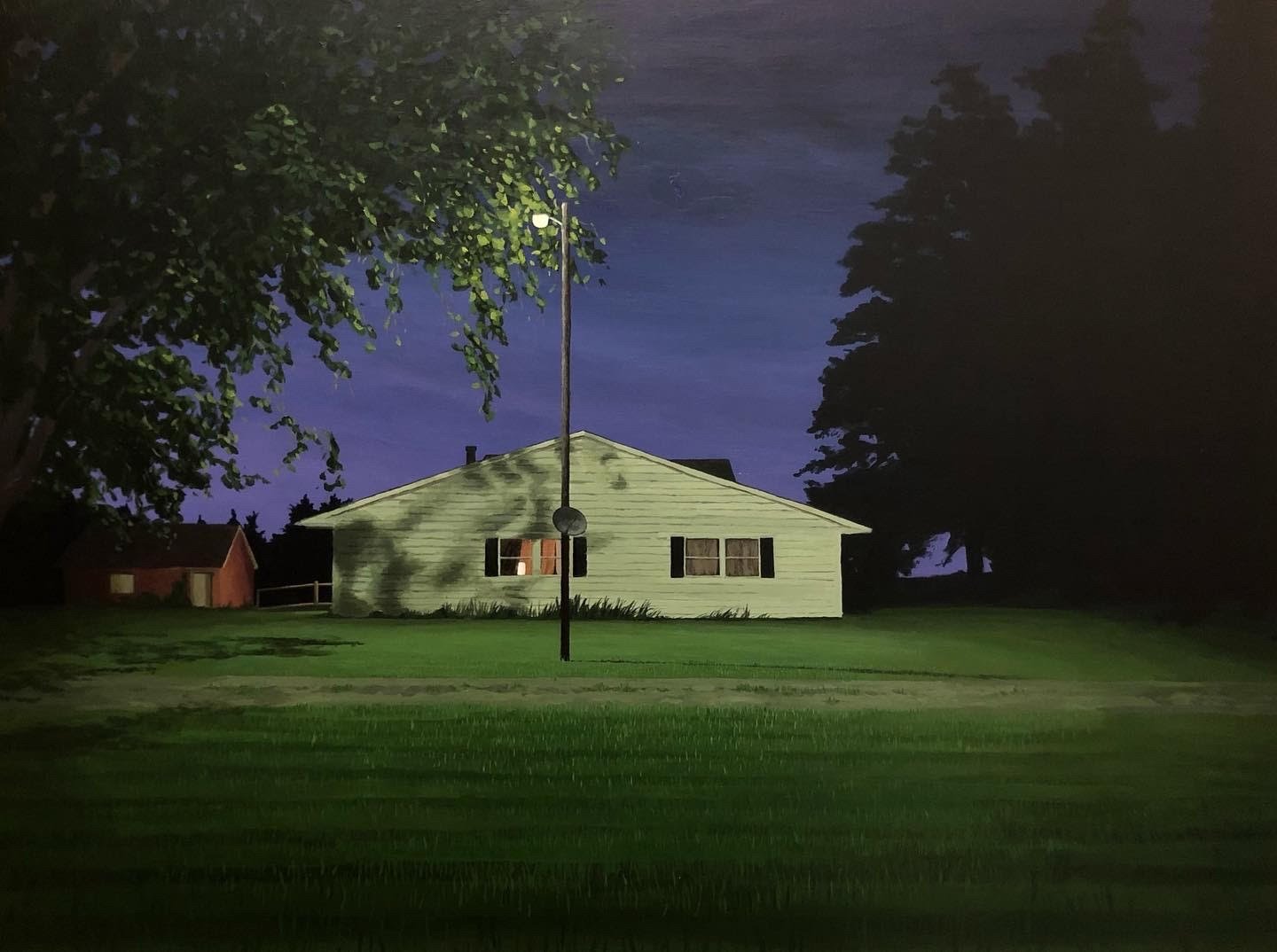

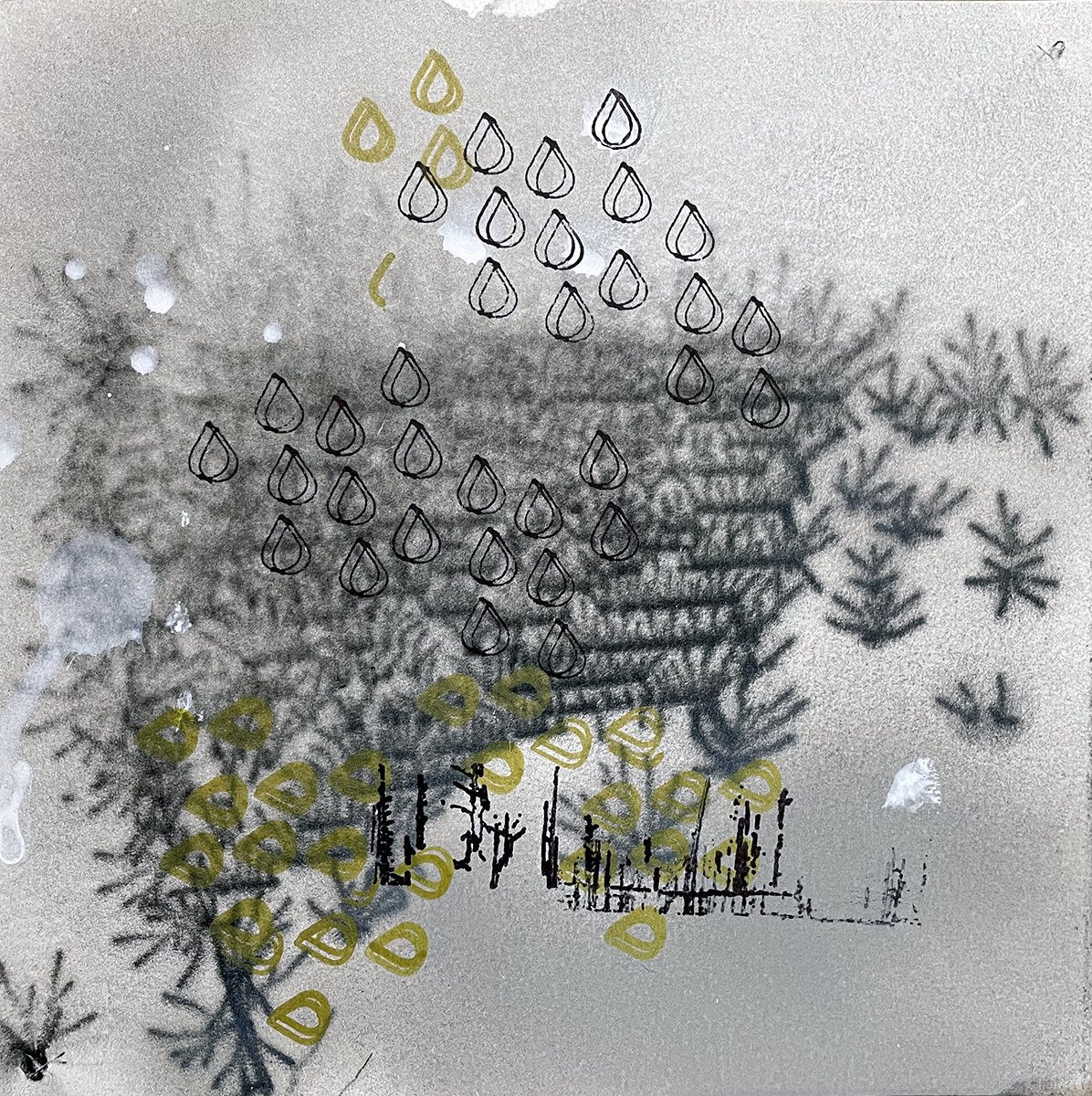

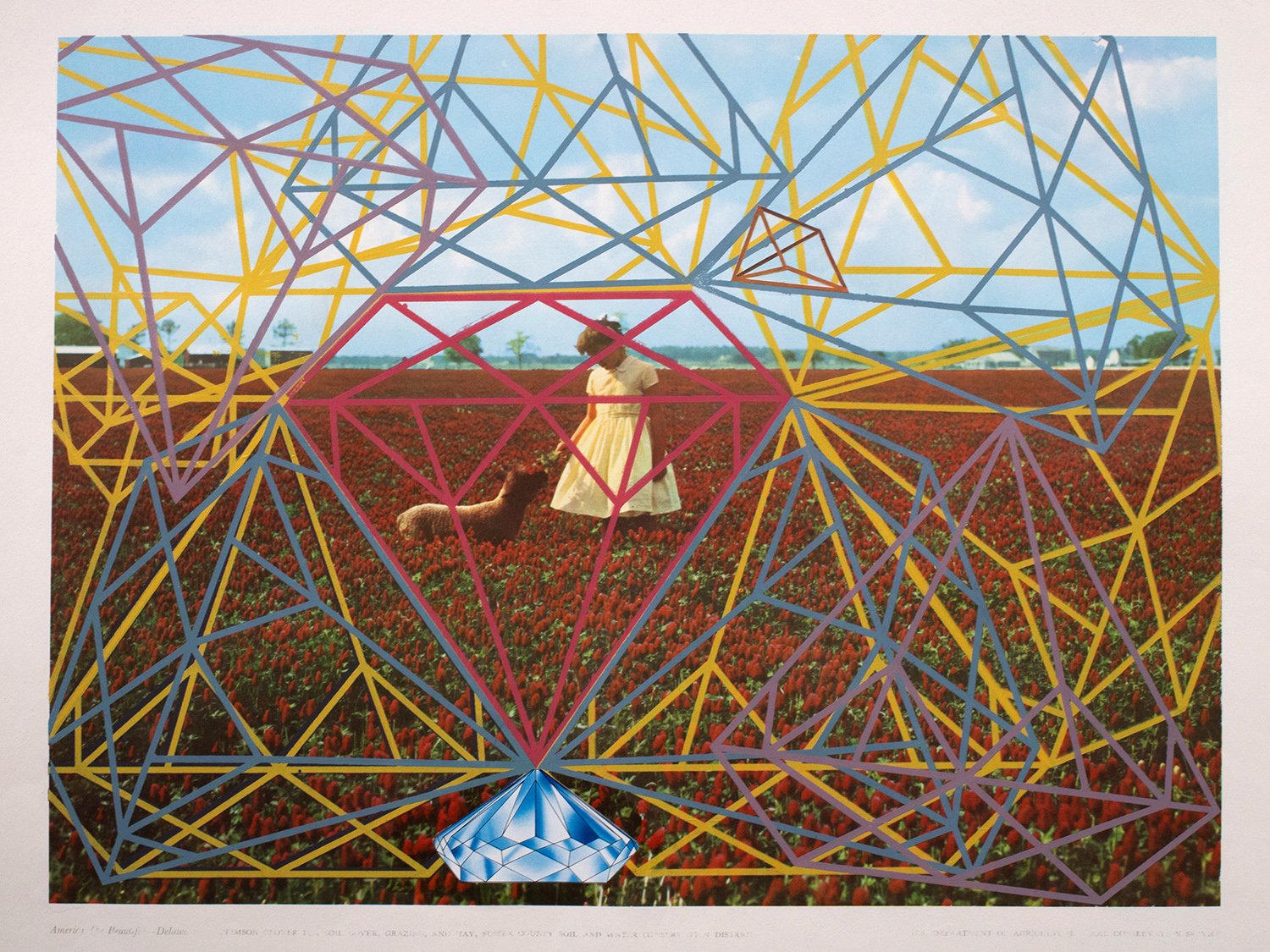

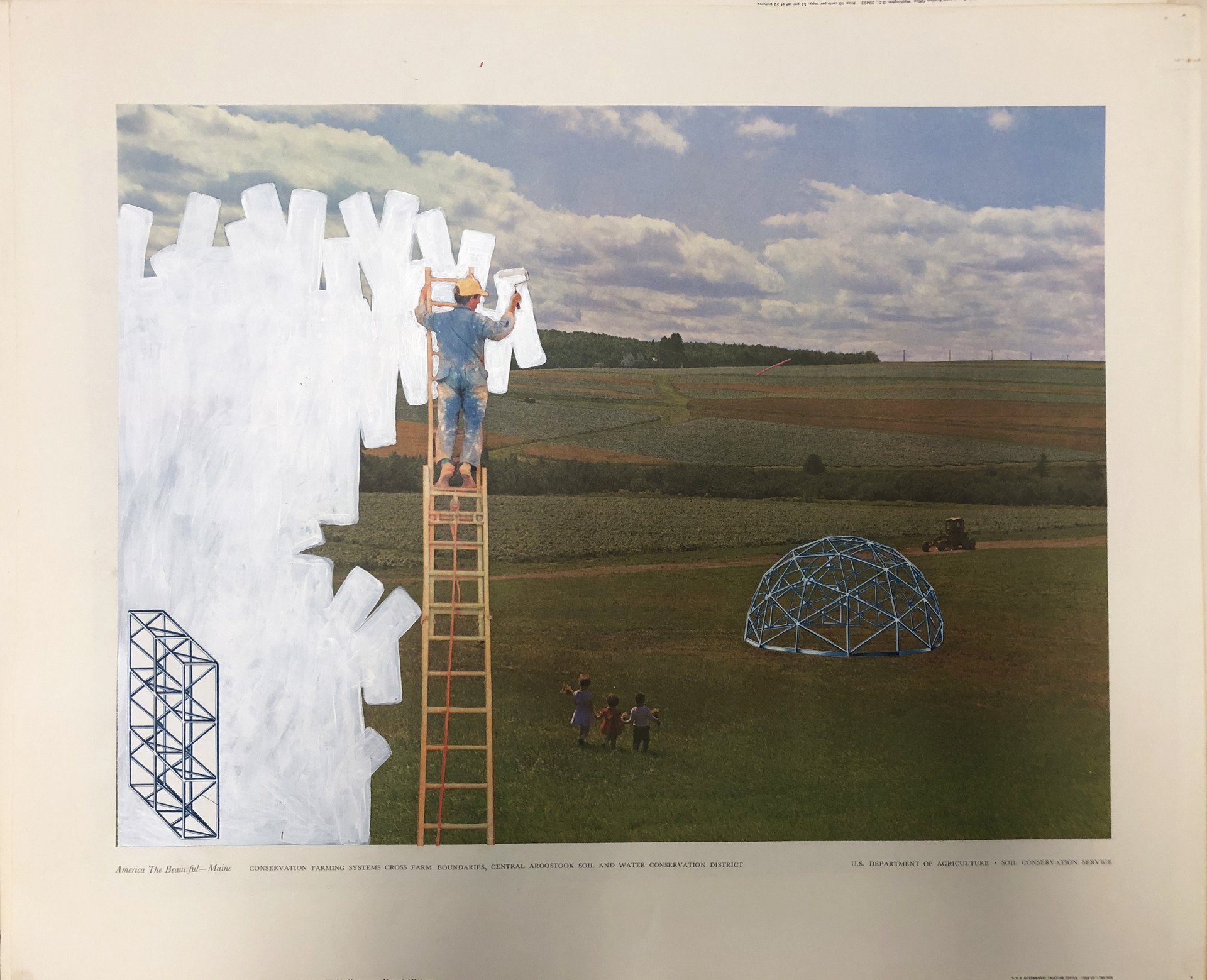

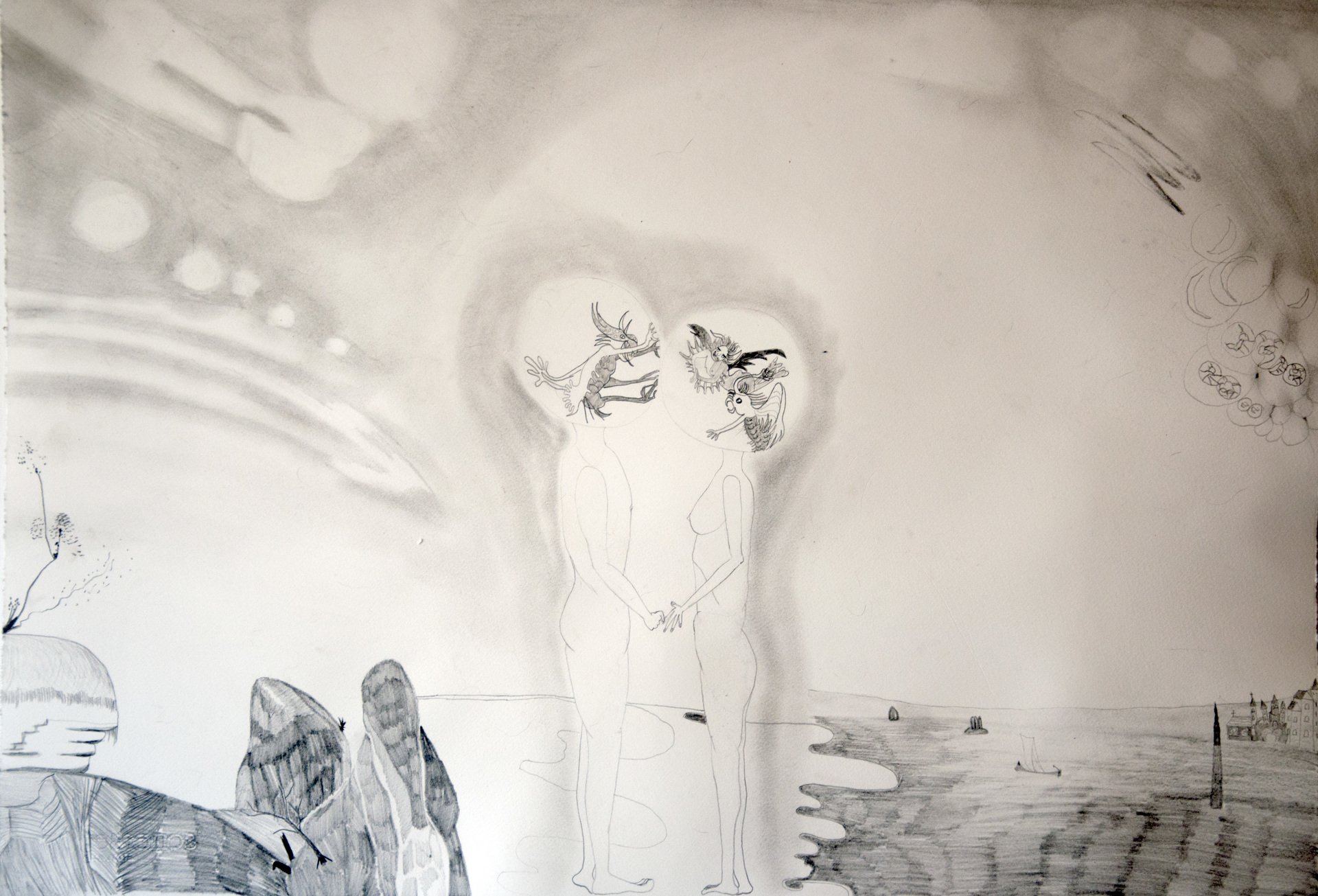

A sense of both real and imaginary place, our changing relationship to the natural world, and the fragility of the human and nonhuman existence permeate the referential and representative works on view. Here are representations of visual “reality,” but less straightforward—more oblique, seen through gauzy hazes, overlaid with a multiplicity of forms, hidden messages and codes. The natural world touches the grotesque, while specific geographic locations—from upstate New York to the Sargasso Sea and to the wider universe, nature (from weather conditions to weeds breaking through the sidewalk)—are grounding forces, but also mystical channels that offer glimpses of other realms of consciousness and potentialities, suggesting alternate realities and ways of seeing. The human figure is often barely visible, a human touch receding in the pictorial field, guided of course, by the steady yet questioning hand of that classic, complex, and most resilient of visual arts practitioners: the painter.