Craft A Force in Contemporary Art

Juried by Annabel Keenan

Curatorial Statement

Craft is the most elusive of artistic disciplines to define. This has been the case for millenia, as craft hovered between utility, function, decoration, and art objects. Common definitions of craft include terms such as handmade and trade, and list examples of weaving, woodworking, metalworking, and glassmaking, among others. A learned skill is often involved, as are specialized tools. In the past (and in some cases still today), craft was often associated with women’s work, in particular textile and fiber art. The more one scrutinizes the term craft, the less clear it becomes. With the rise of modern art and the increase in mixed media works, interdisciplinary practices, and specialized techniques–and even more so as contemporary art evolves–the boundaries between art and craft have become increasingly nebulous if in existence at all.

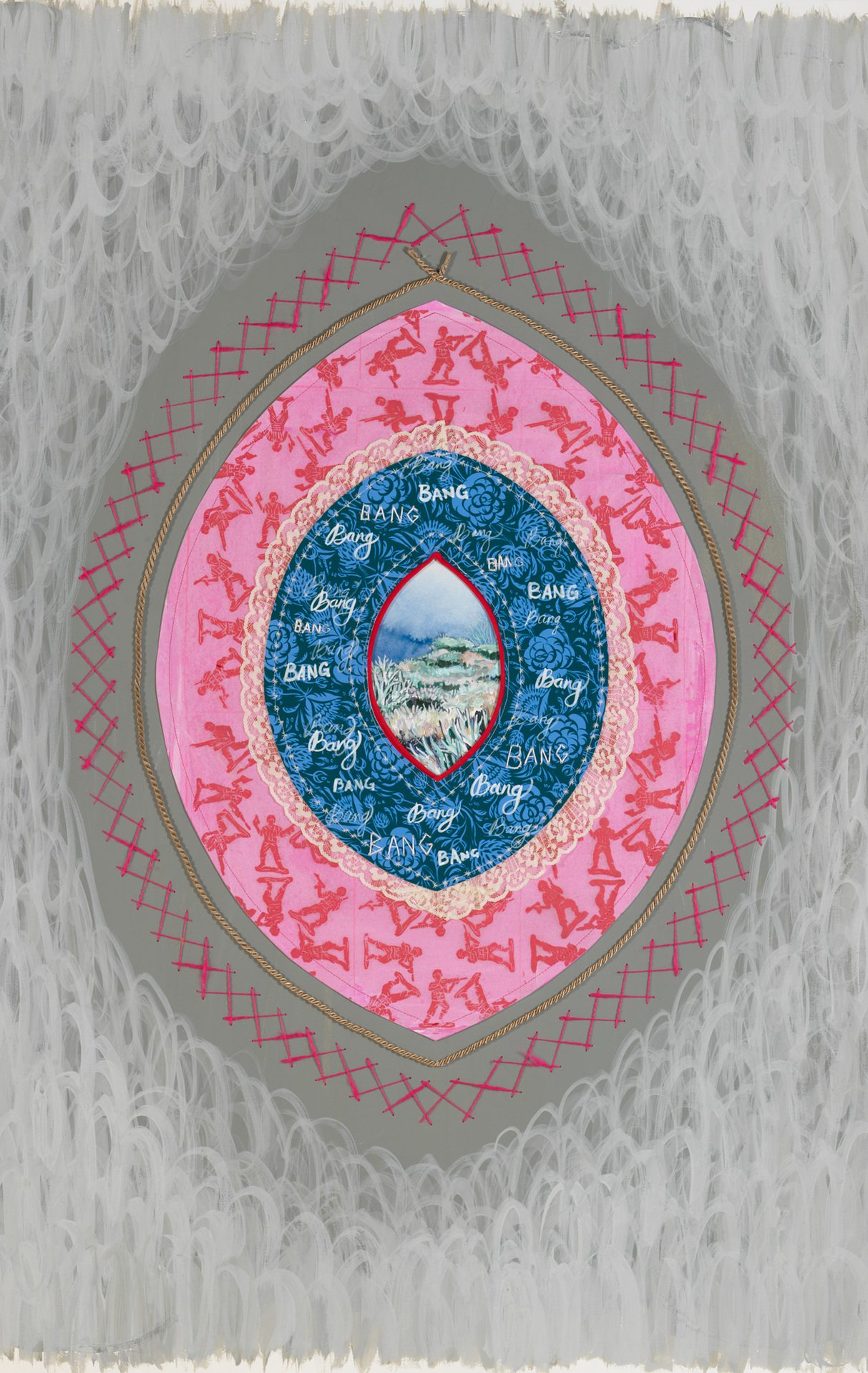

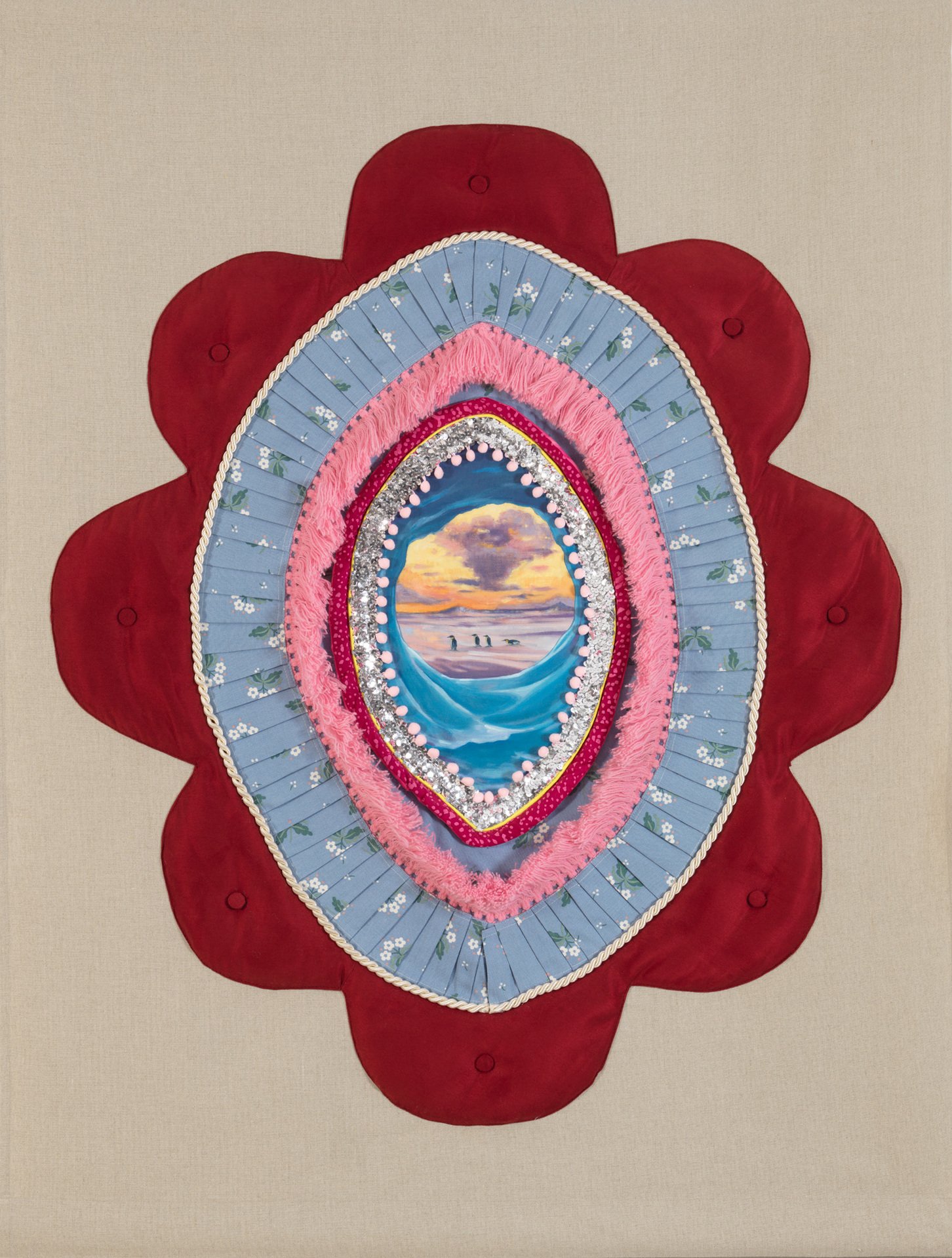

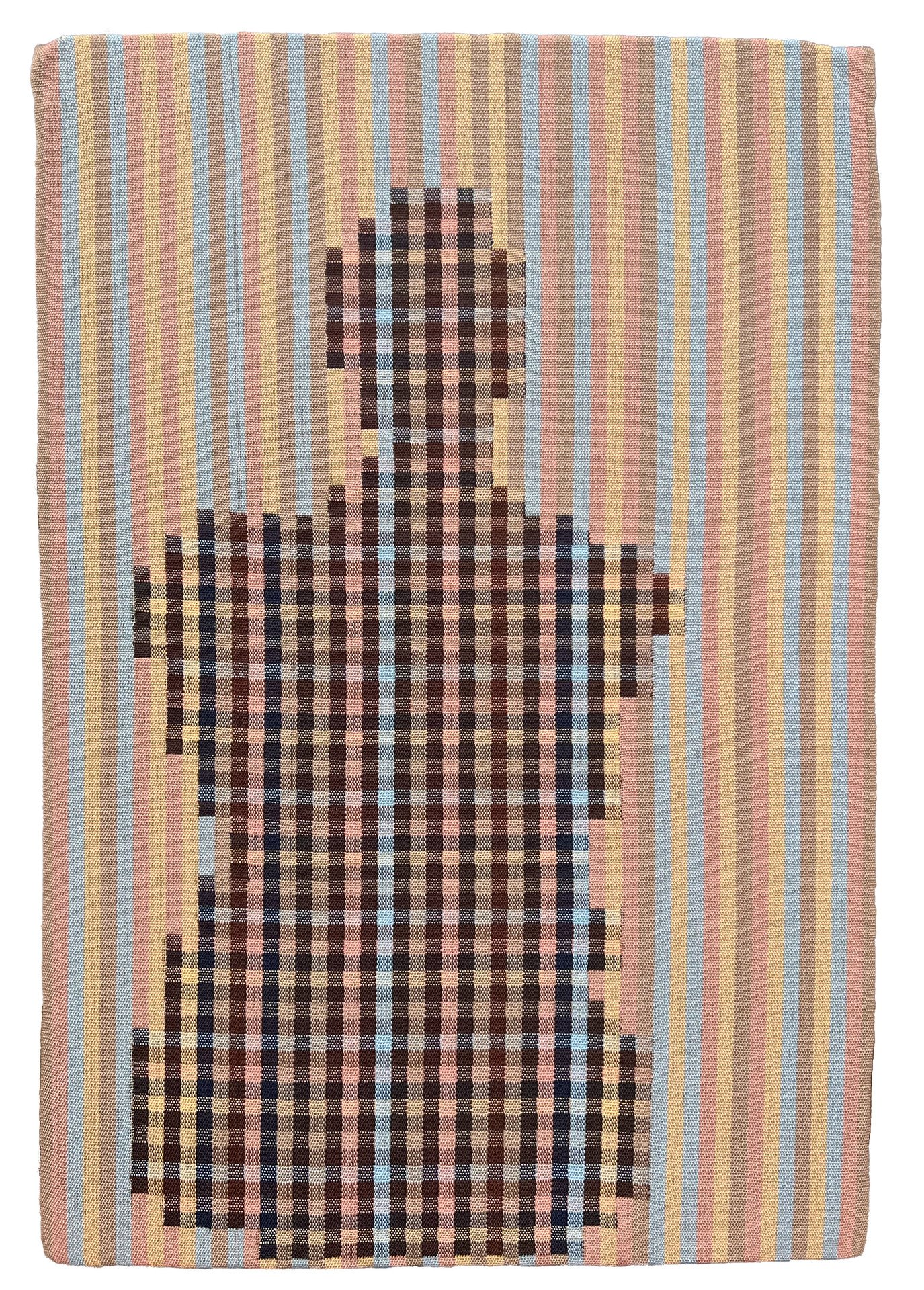

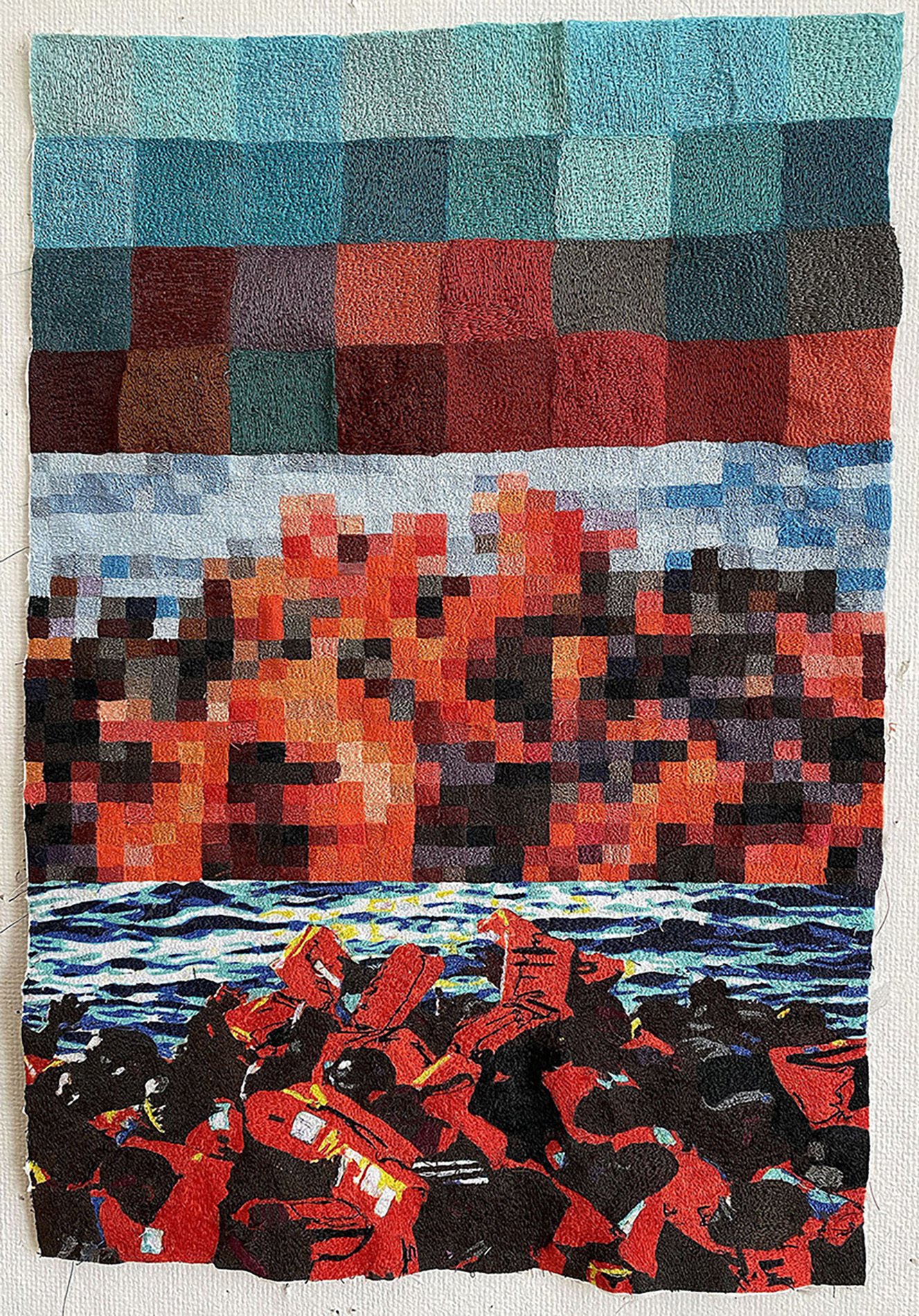

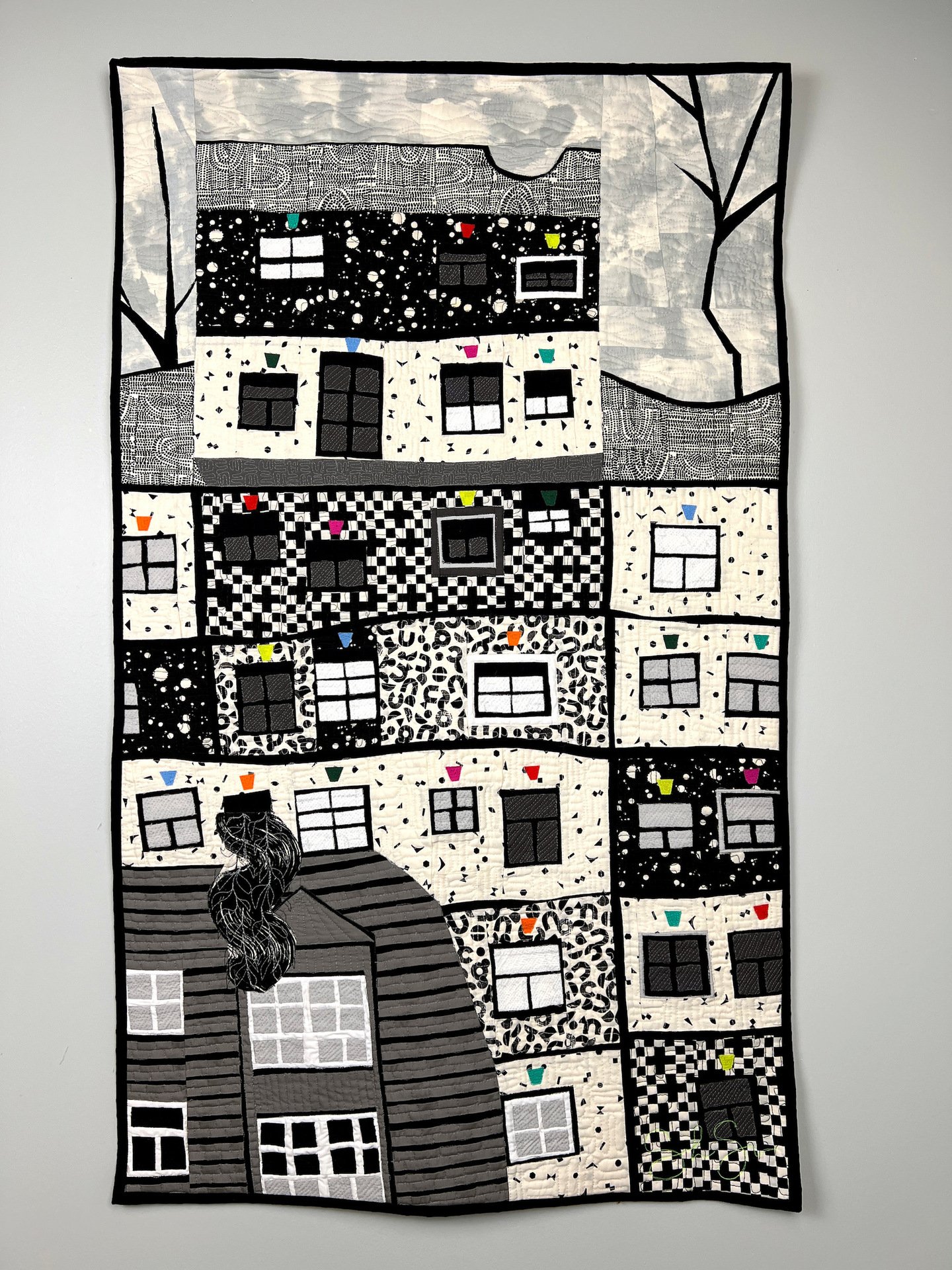

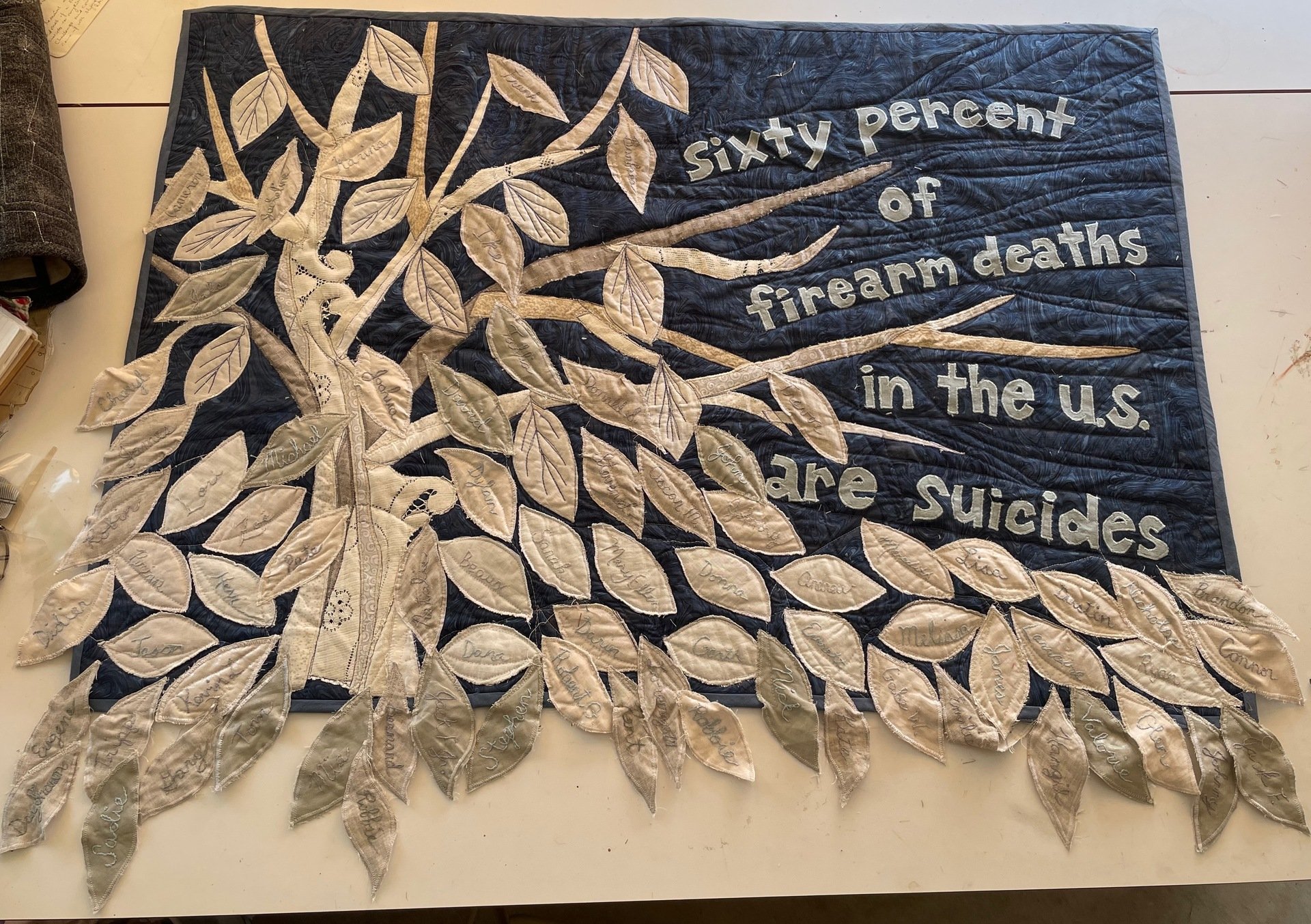

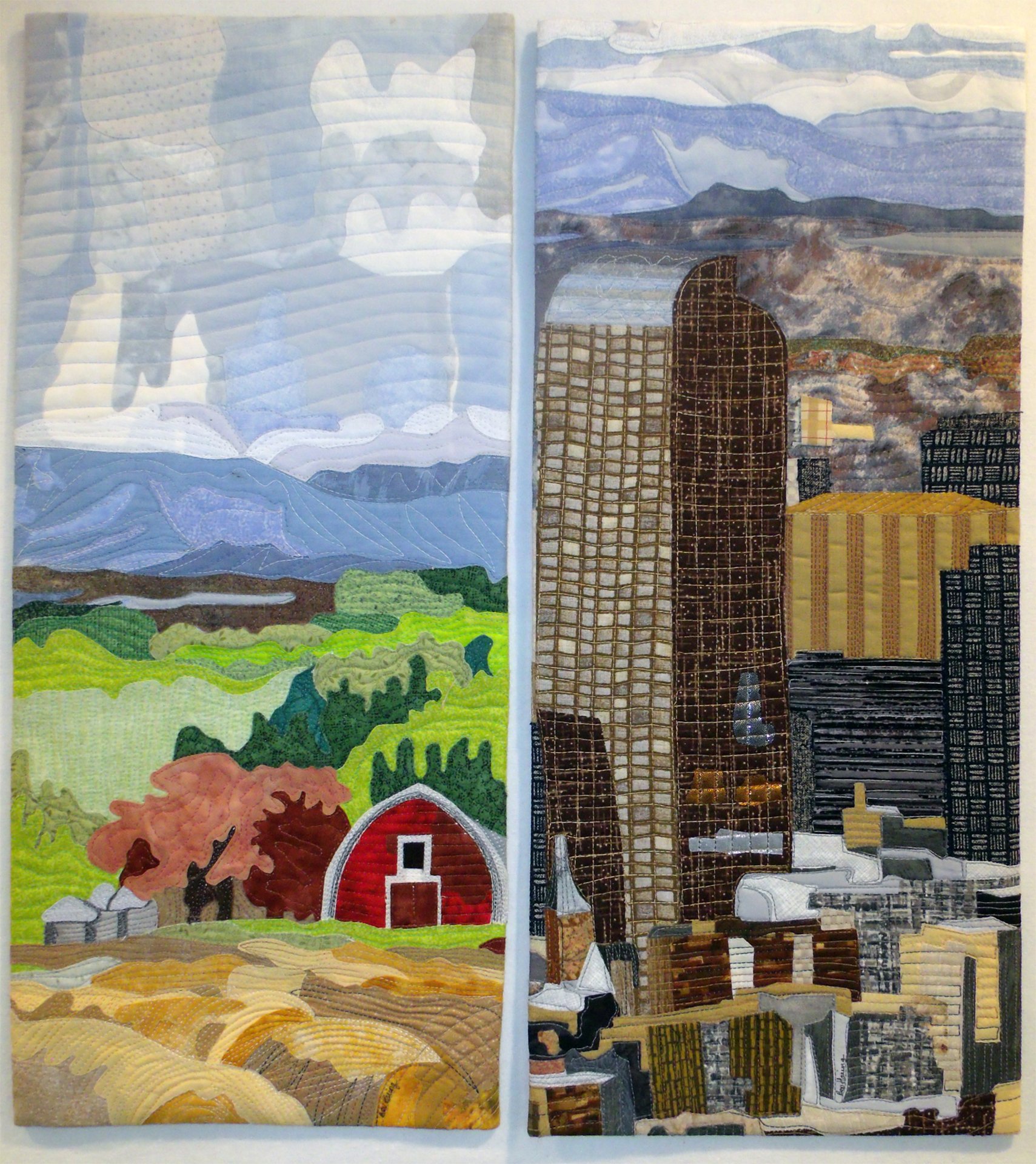

The submissions for this exhibition prove how dynamic the field of craft is today. Some artists combined disciplines to challenge the possibilities of each, while others zeroed in on specific crafts, limiting themselves to just one to showcase their skill. These works gave rise to the first theme of the show: pushing the boundaries of craft and contemporary art. The various approaches to craft represented in the submissions also showed an interest in rethinking utility, while several other artists considered the ability of art to hold memories. From sentimental and nostalgic imagery to explorations of heritage, the link between art and emotions rings true throughout the show. The final theme, and one that seemed to permeate nearly every other section, centers on craft as a form of activism. In this, charged works present powerful messages about the state of the world today, including global issues of climate change, as well as more national and regional concerns of bodily autonomy and gun control.

Many works in the show fall into multiple categories, a reflection of the dynamic practices each artist has built. What is clear is that the future of craft does not look like the craft of previous generations. Though some themes resonate across time–form versus function, objects of nostalgia, and art as activism, in particular–the approaches artists are taking today are bolstered by innovations in technology, culture, and our interconnected society. – Annabel Keenan

I. Pushing the boundaries of craft and contemporary art

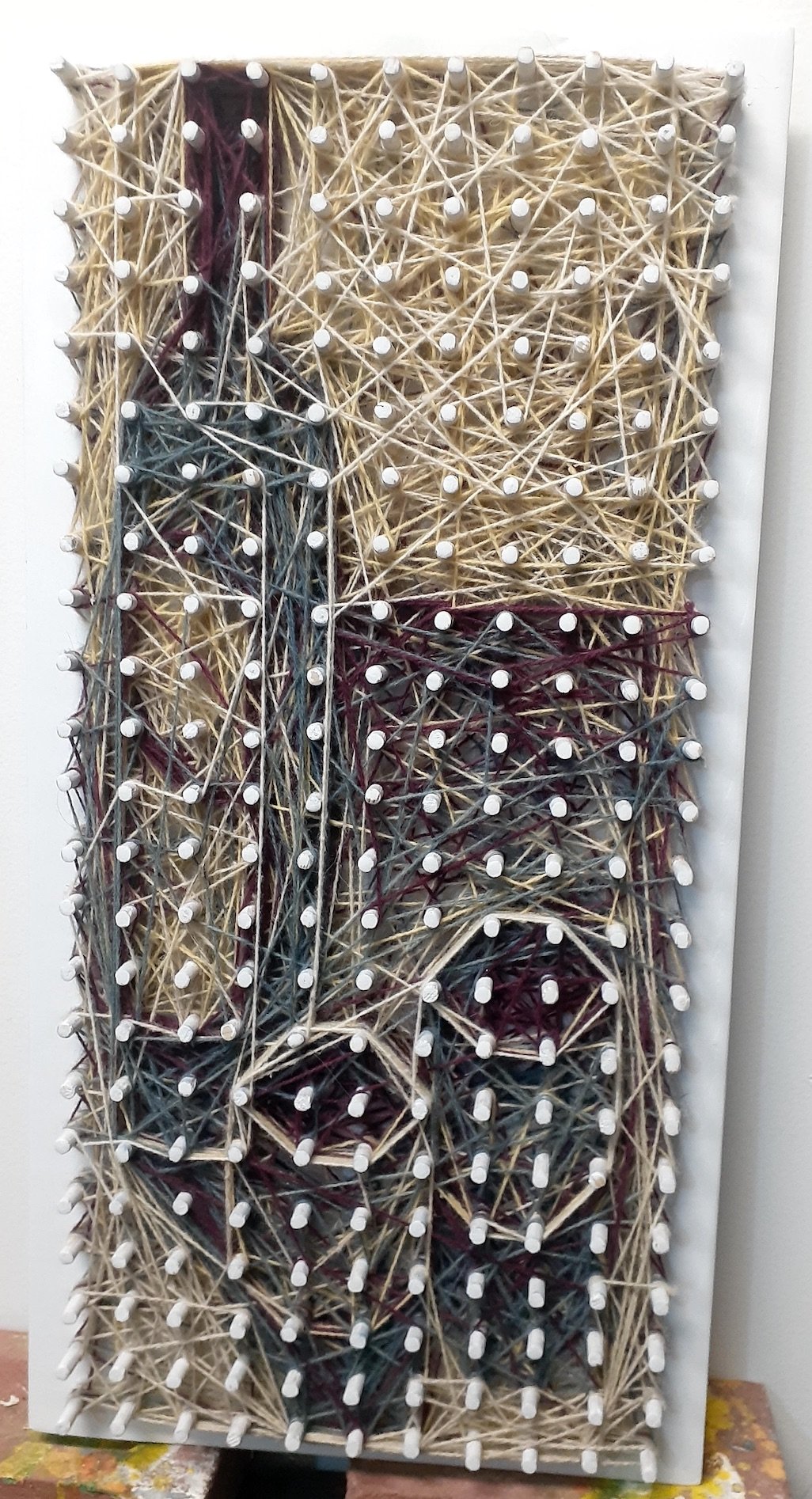

Throughout the show, several artists emerged as innovators in craft, rethinking traditional materials and techniques to push themselves and the definition of craft. Many of these artists blend materials or use them in ways that show both immense skill and creativity. In skillfully made mixed media textiles, David Schleifer & Tracy Gilman rethinks traditional weaving methods by using SJOOW cables, a nod to the ubiquity of materials associated with technology. Similarly, Elizabeth Runyon employs traditional Appalachian basket weaving techniques to create woven sculptural forms made of reed and seagrass. Visually stunning and technically complex, Runyon’s work often reflects on larger issues, such as grief, death, and the everyday burdens we carry. Also pushing the boundaries of material is David Stevens, whose meticulous sculptures seem to defy the makeup of wood.

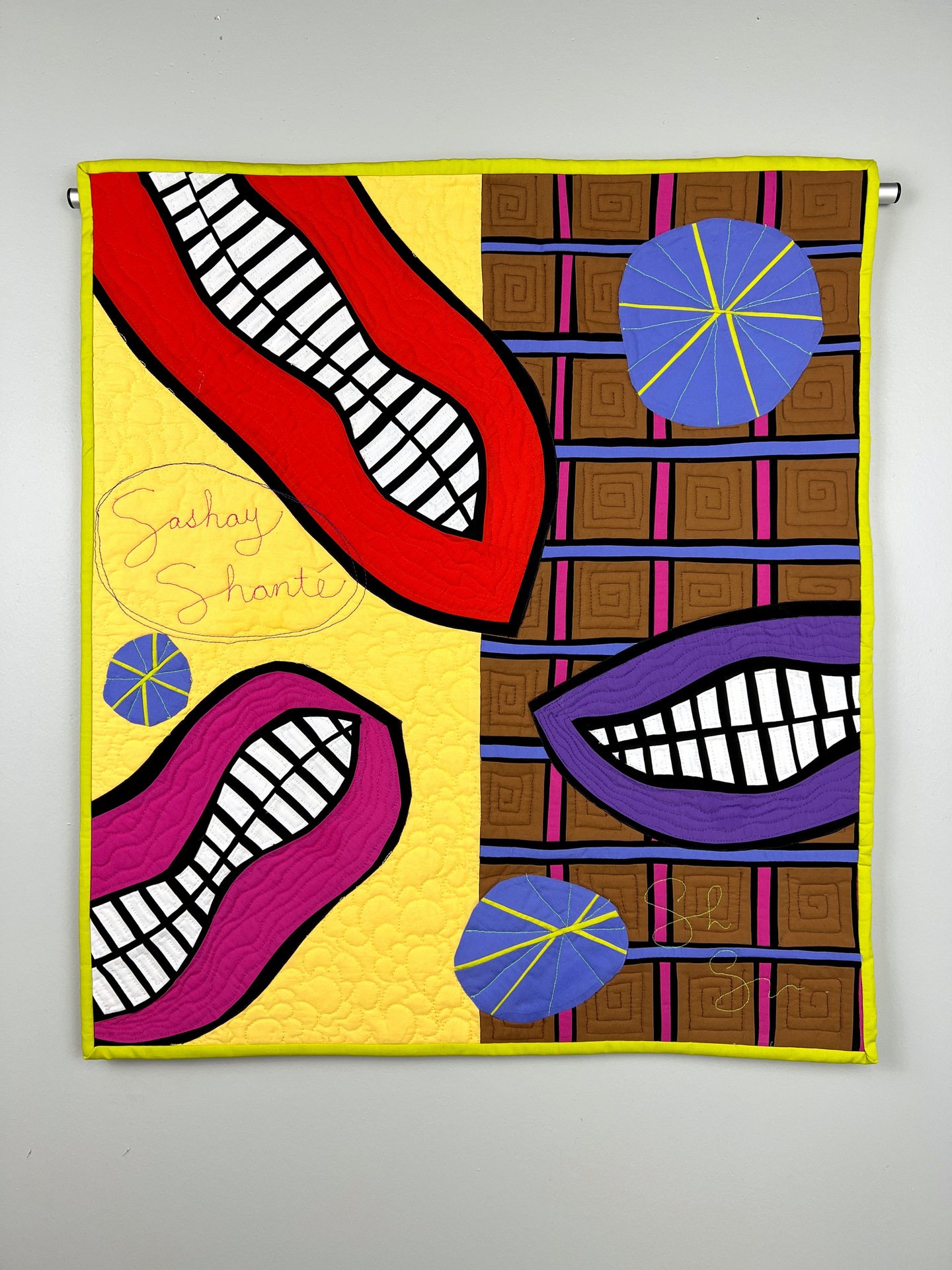

Embracing technology, Kristen Applegate uses AI-generated imagery on hand-built stoneware, employing the contemporary tool in the ancient practice. Using machines to enhance her improvisational textile works, Sarah Spencer draws from various inspirational sources, in particular popular culture and music.

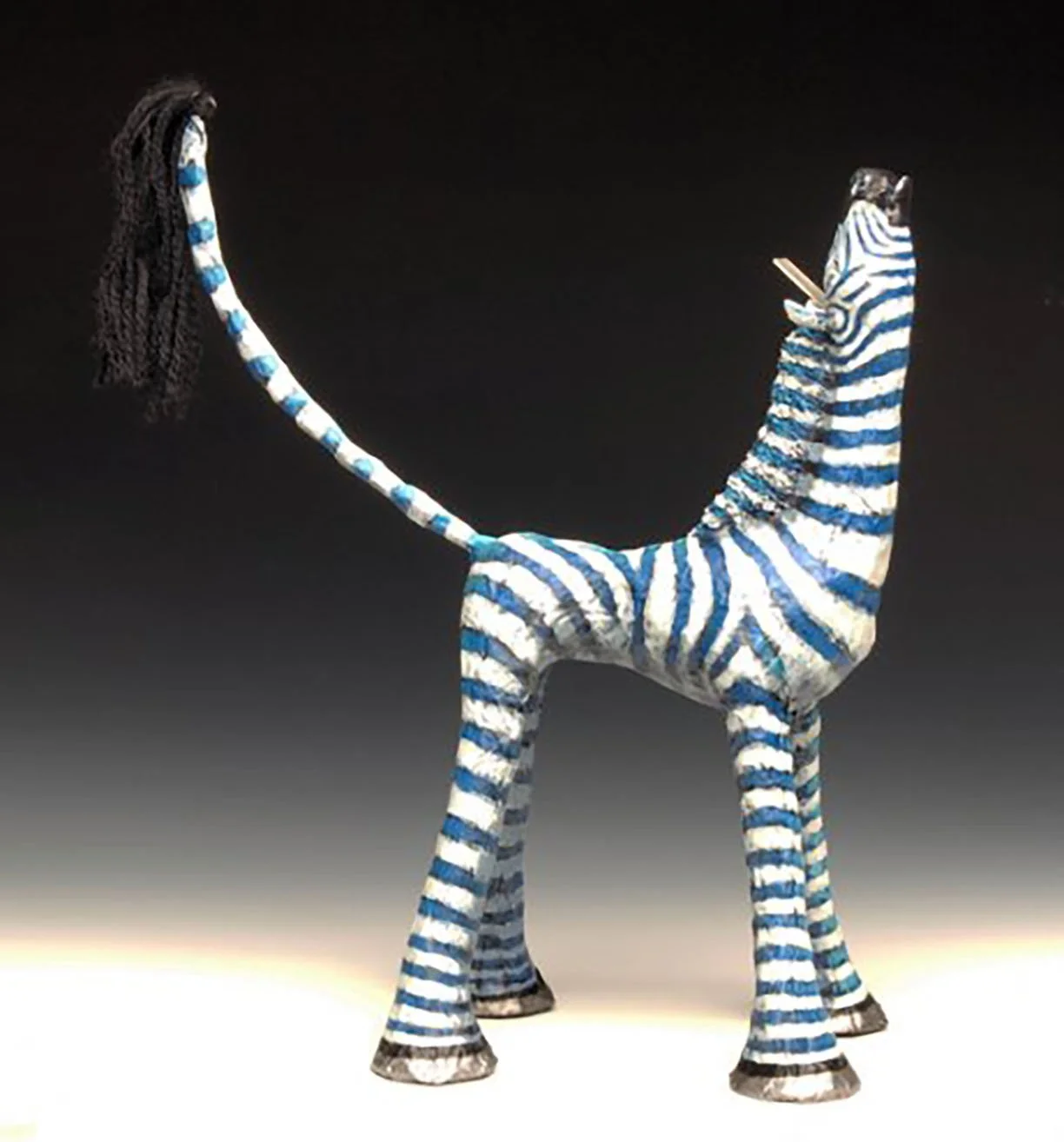

Creating intricate sculptures using a variety of crafts, such as glass and ceramic, are Victoria Rosenblatt, Lydia Thompson, and Lisa G Westheimer. Also pushing the boundaries of craft and sculpture is Sudie Rakusin, whose playful creatures are made of papier mache and beading. Showing the artistic capacity of glass are Anna Guarneri, who creates architectural, stained glass works, and Christine Barney, whose abstract compositions are made from furnace formed glass block cut, ground, polished, and rebuilt into new forms. Also using glass is David Schnuckel, who builds geometric forms out of individual goblets, showing how something with a simple exterior can be composed of a complicated interior.

II. Utility in craft

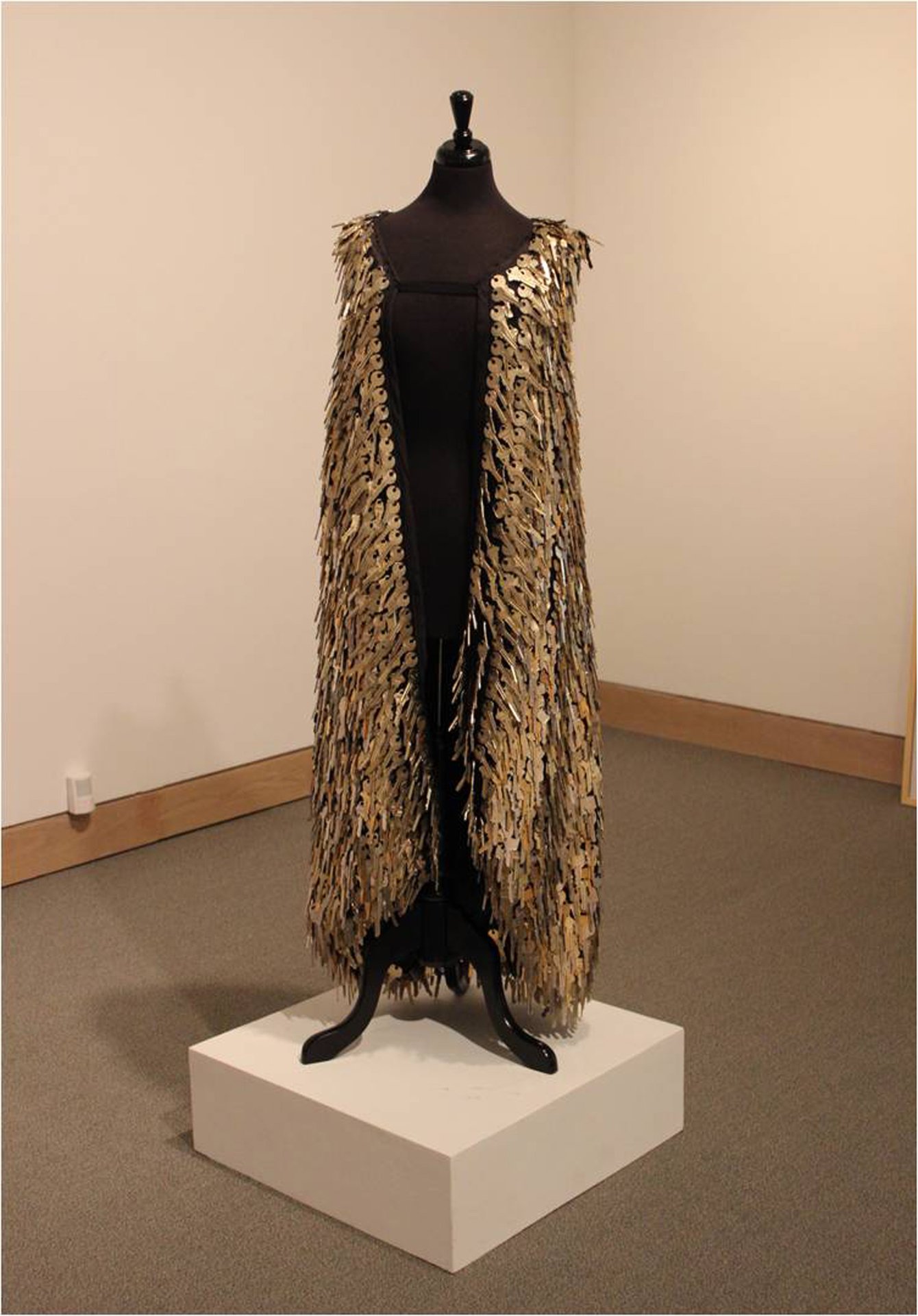

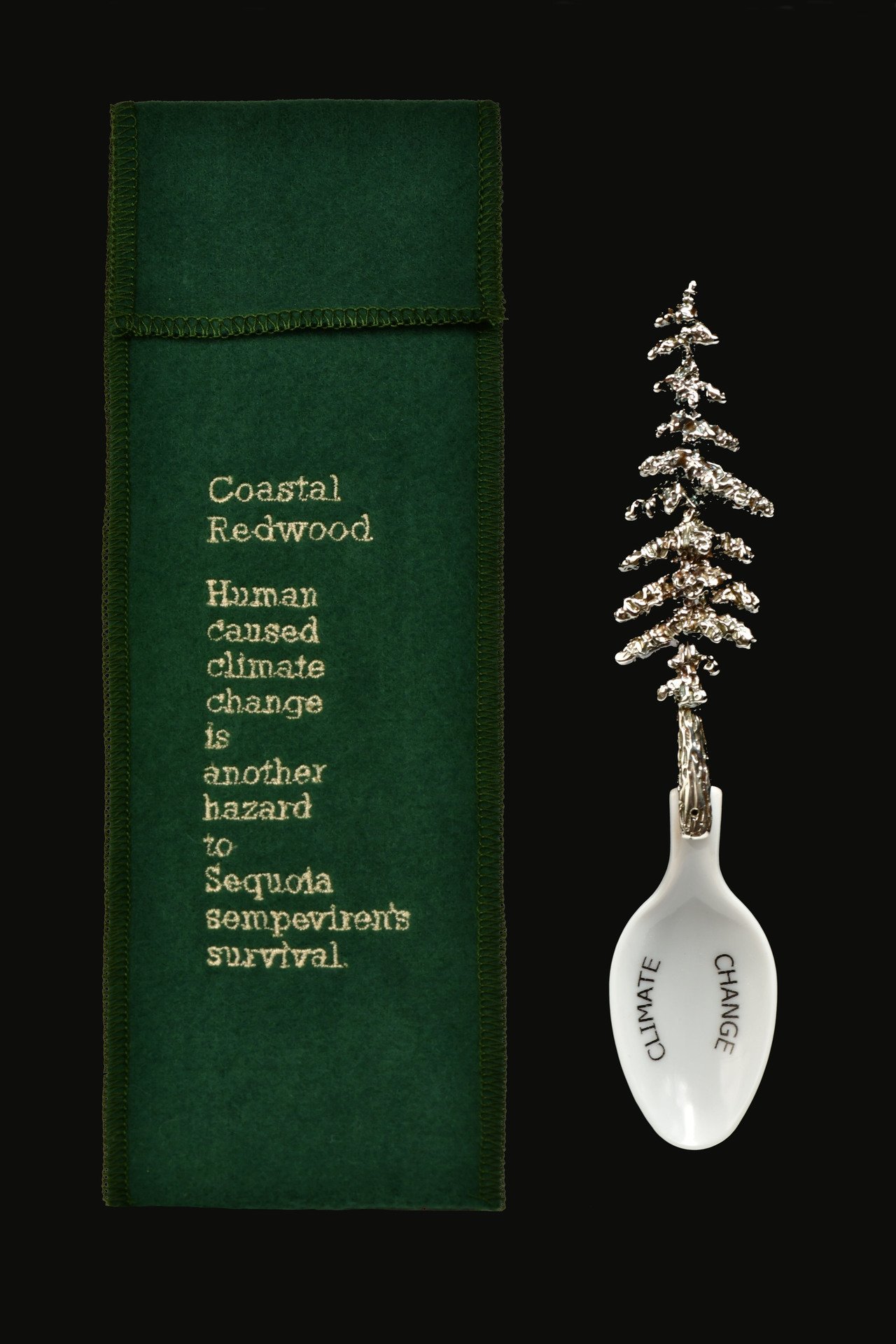

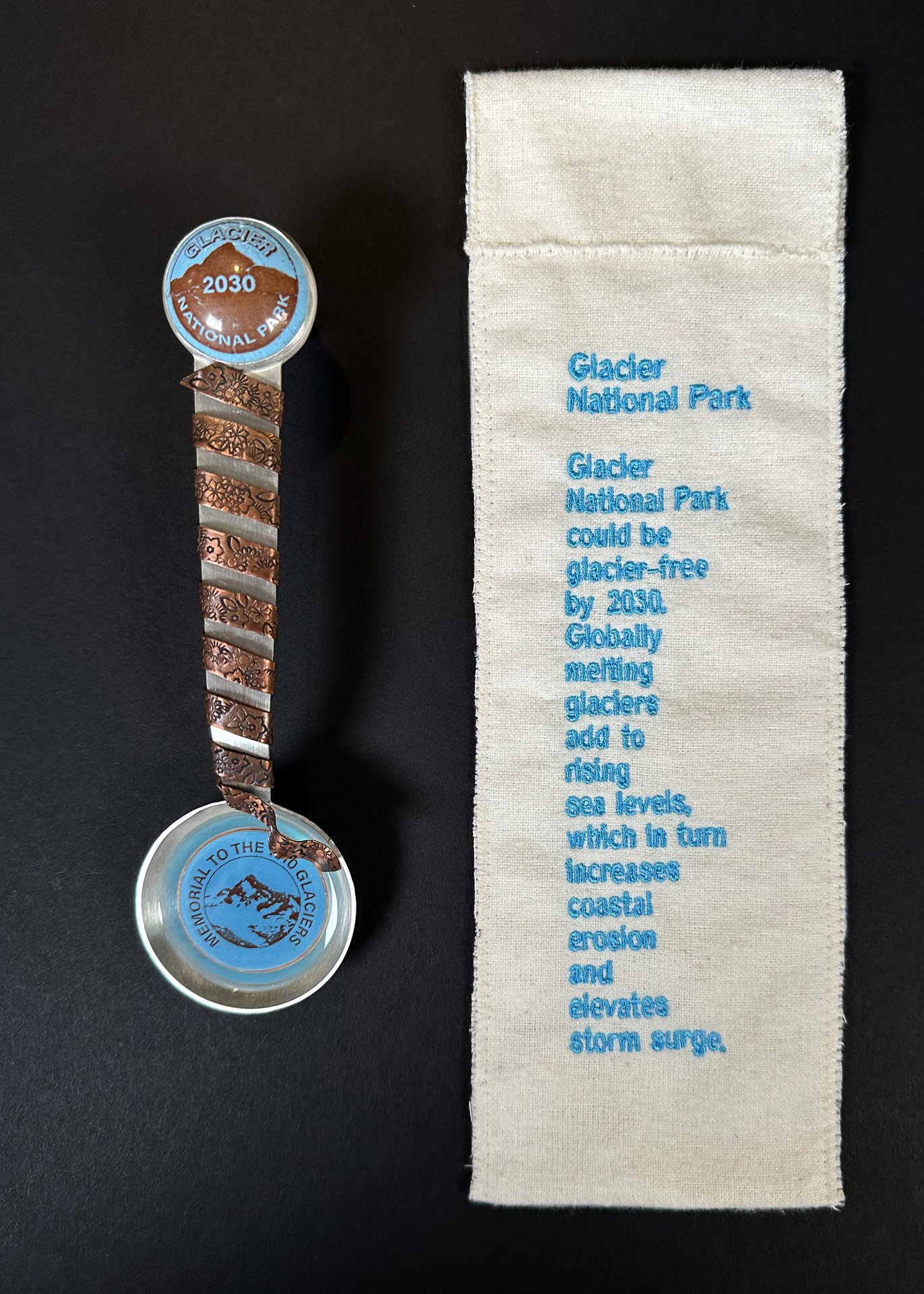

Many forms of craft derived from the need to create functioning objects, such as furniture and clothing. Utility and form in craft are often determined by function. As craft and contemporary art evolve and overlap, artists push the boundaries of form, utility, and function. Rethinking historical forms and materials is Rebecca Arday, who considers the body and conventions of tailoring clothes, applying them to her design of the American Windsor chair. Also innovating traditional furniture forms is Peter Scheidt, seen in his chairs that transform to reveal hidden components, including unexpected storage. Making a statement about waste, Joyce Watkins King created a vest from over 4,000 recycled keys that weighs 80 pounds, the average weight in clothing that Americans throw out annually. Also creating a functioning object is Nancy Slagle, whose spoons are paired with found objects, anti-tarnish cloth, and embroidery. Named after issues like climate change, Slagle, like King, points to the power of craft to address broader social concerns.

III. Memory, nostalgia, and the emotional weight of art and objects

For many of the artists in the show, their practice relates to nostalgia, memory, and the emotional weight of art and objects. They use craft as a way to heal, remember, connect with their ancestors, or release a burden. A poignant example is Oli Boyer, whose work represents aspects of their transition, such as a nearly 11-foot long weaving made with materials from this process, including plastic piping and medical gloves used to drain their chest after top surgery.

Also highlighting the healing power of art is Marcie Ziskind, whose wet felted and hand embroidered sculptures resemble human hearts with flowers and vines growing through them. Similarly, Cathy Abbott combines a variety of materials, including threads and Uzbek amulets to meditate on the healing capacity and mythical significance of objects.

In a portrait of their late dog, Snoopy, artist Terri Frew considers the legacy of stuffed toys in memorializing loved ones. Referencing The Velveteen Rabbit, Frew embraces both the imperfections and beauty of Snoopy. Imbuing a nostalgic, lighthearted message in their work is Jamie Scherzer, whose keychains recall childhood crafts, as well as Elizabeth Bonner, who creates playful ceramic animals. Similarly, Rhian Swierat’s mixed media pieces with pressed wildflowers reflect the practice of collecting and pressing flowers that the artist has done since childhood. As they fade over time, the flowers act as a metaphor for life and death.

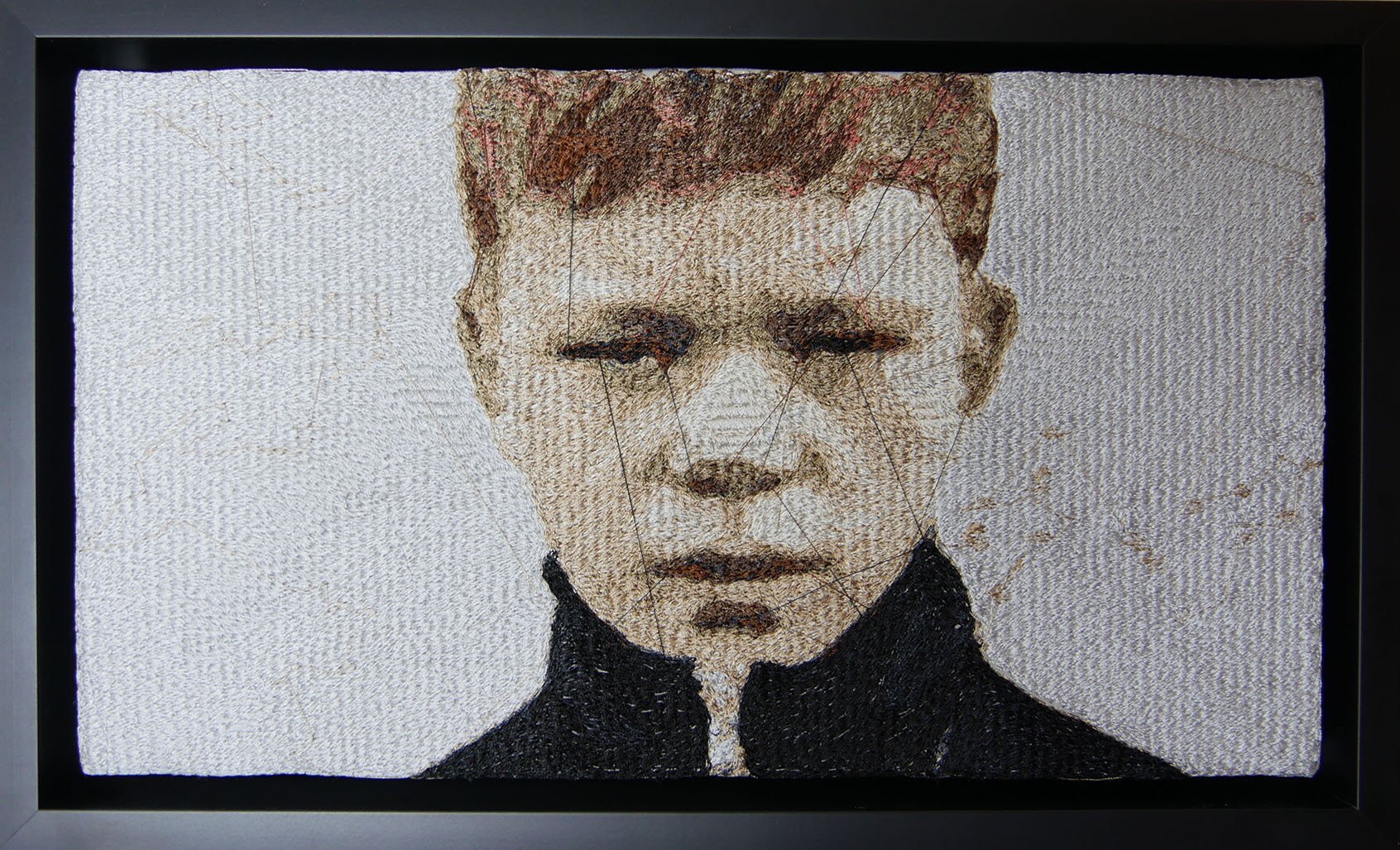

Paying homage to maritime myths and traditions are Blair Martin Cahill and Emmett Barnacle, the latter through intricate, colorful ships made of cast crystal, Mayan walnut, steel, and aluminum. Blair Martin Cahill also memorializes the nomadic Irish people known as Travellers, imagery that parallels the emotionally charged knit wool portrait entitled Memorial (2023) by Eric Dwyer and intimate still life by Marcos Hernandez Chavez.

IV. Craft as activism

Craft has always been used to signify the beliefs or interests of the owner. From personal adornments, such as clothing and jewelry, to visual displays with specific messages, such as flags and quilts, craft is often at the core of activism.

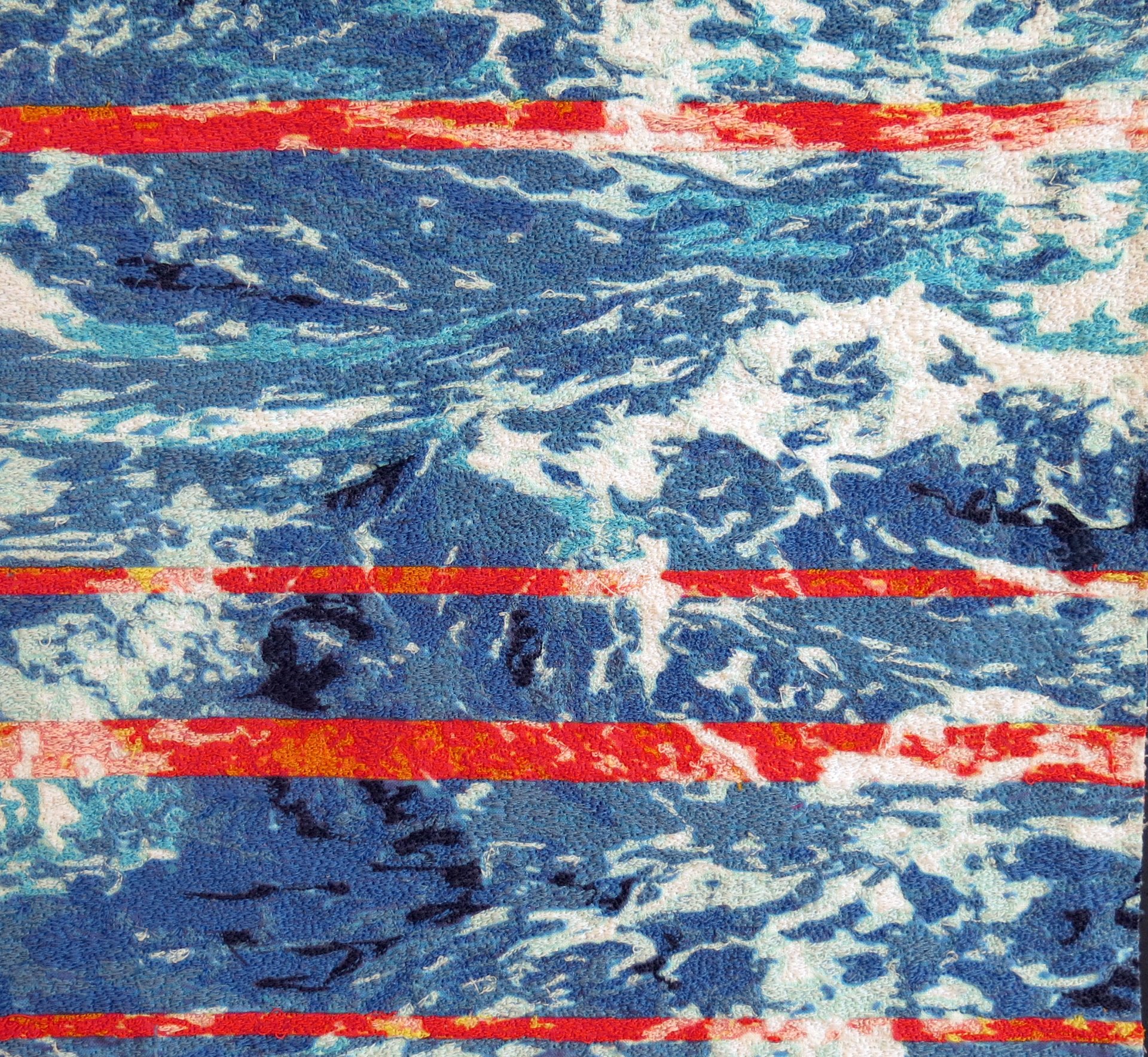

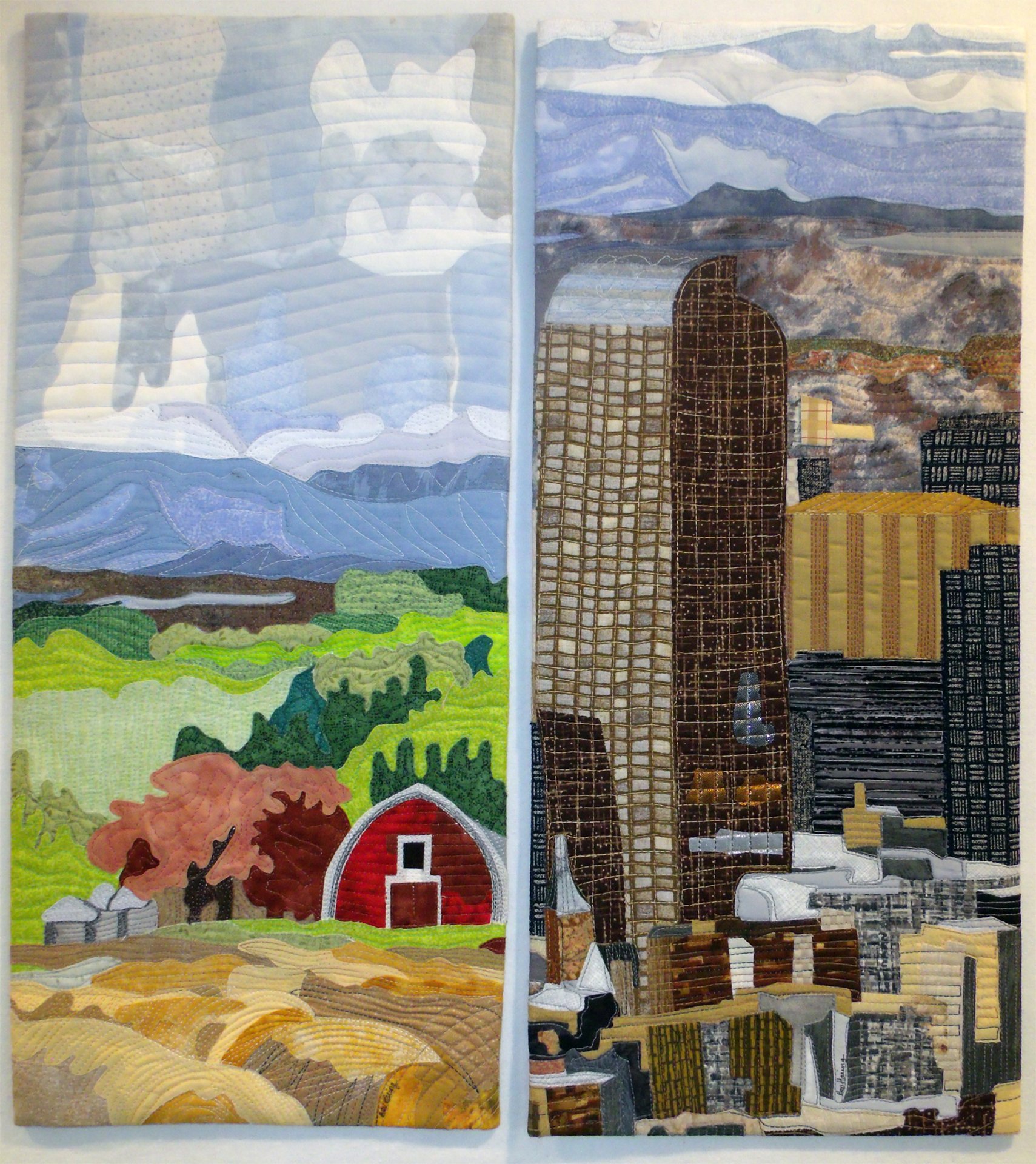

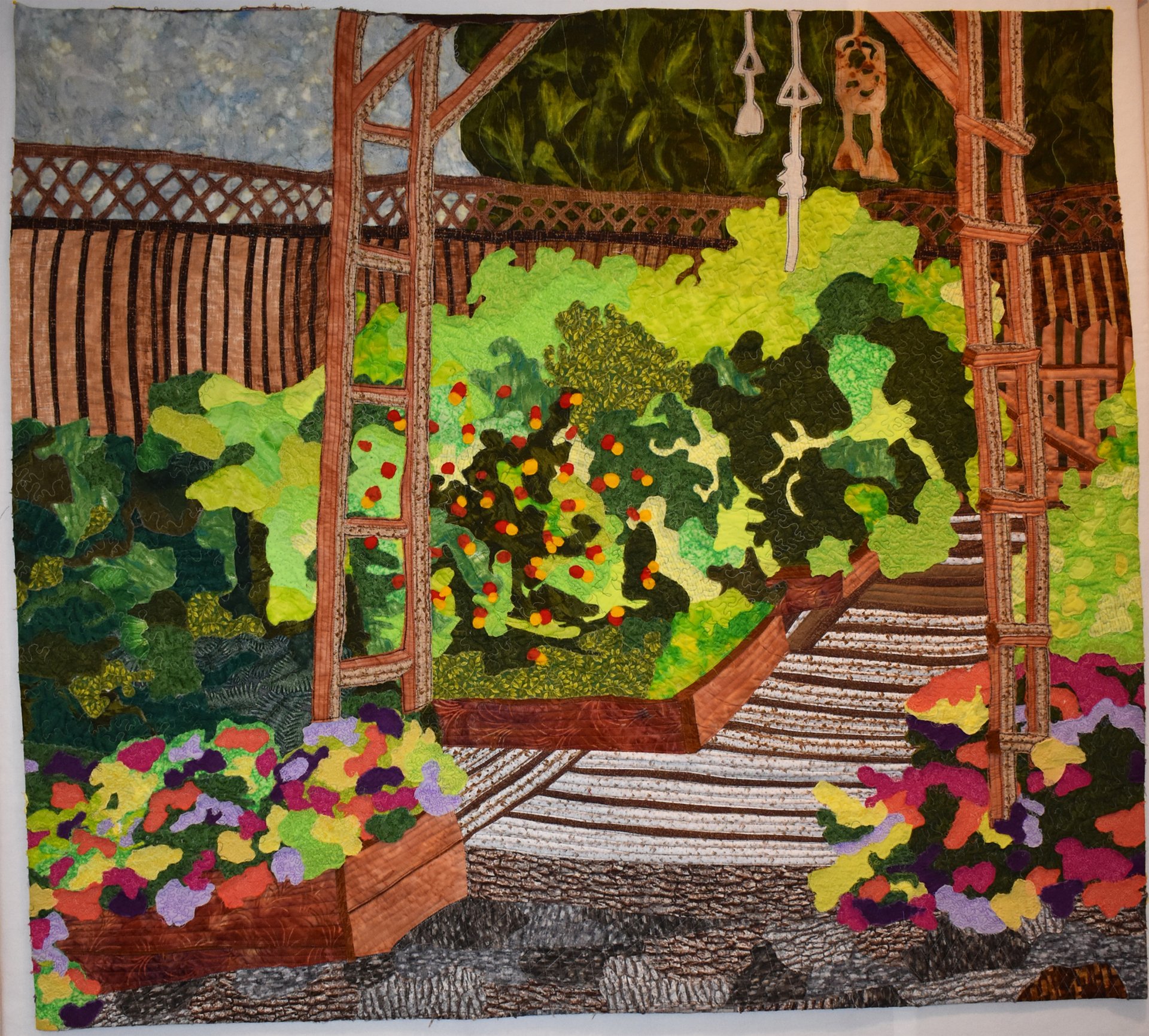

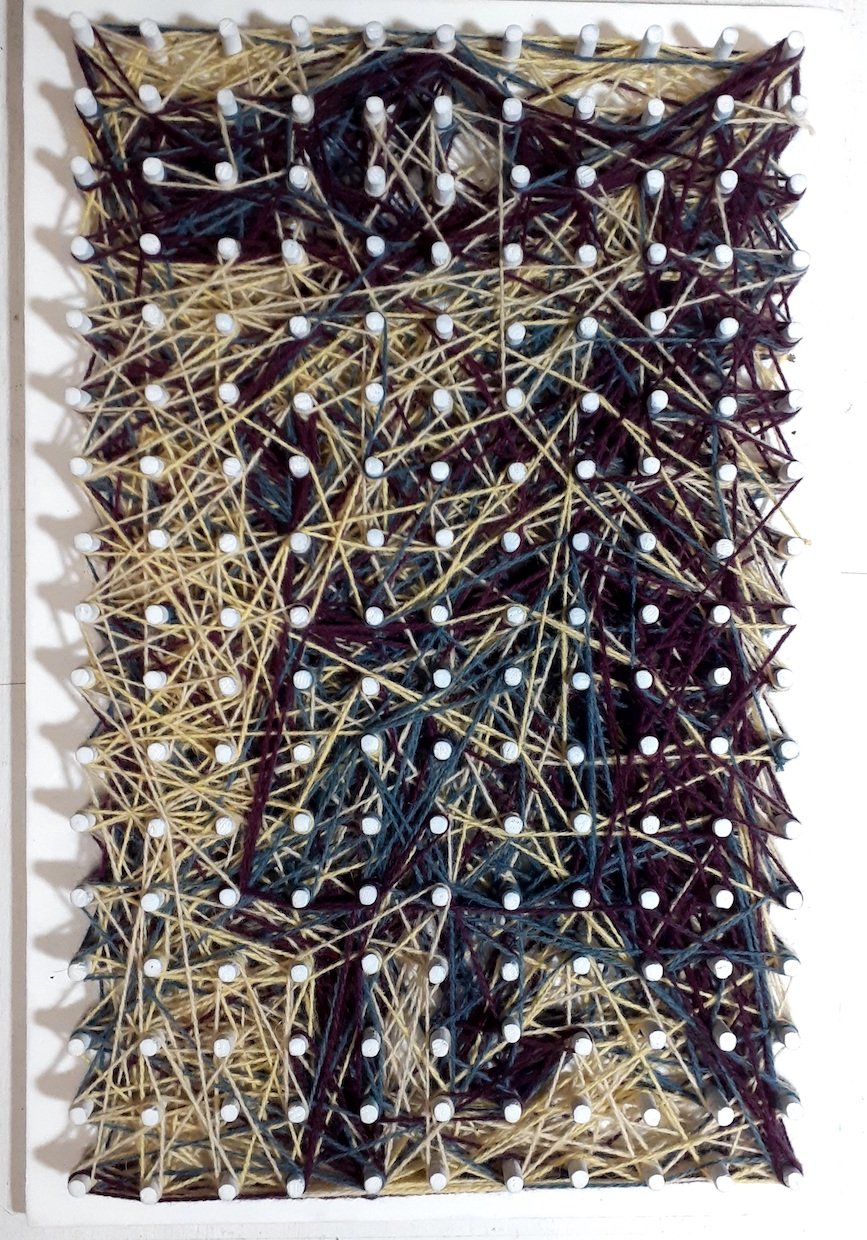

Included in the artists who exemplify this tradition are Mary Babcock, whose mixed media, abstract work consists of repurposed materials, such as fishing ropes and lines to draw attention to the social and environmental impact of deep sea mining. Similarly, Nina K Ekman’s monumental tufted deadstock yarn palm tree addresses the consequences of the palm industry on the planet’s resources, in particular forests. Also drawing attention to the myriad environmental and human repercussions of climate change, urban development, and migration are Ashley Cecil, Bev Haring, and Margaret Jo Feldman, whose works are complemented by Helen Duncan’s stunning porcelain and wire sculpture that reflects the beauty of the natural world.

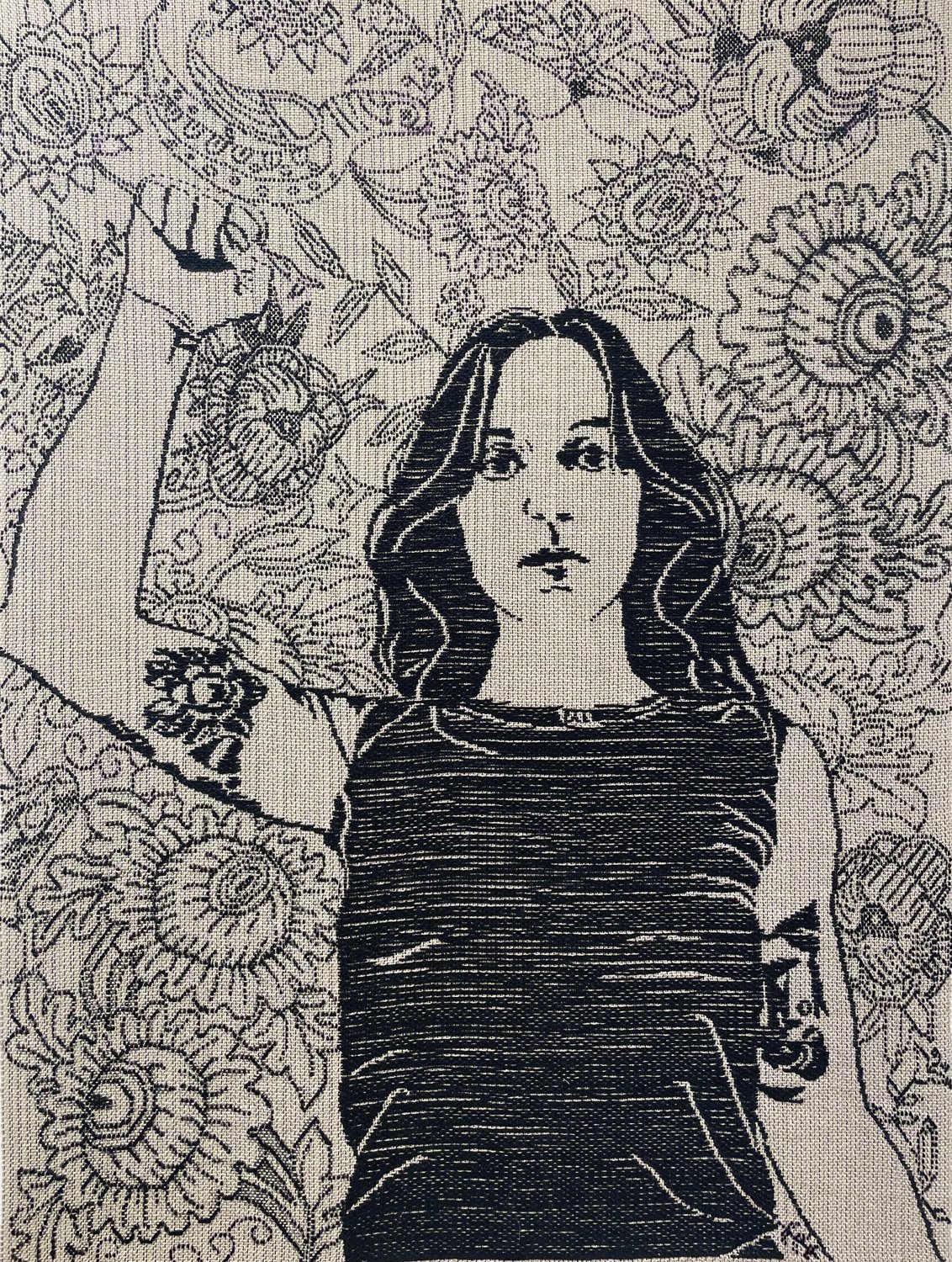

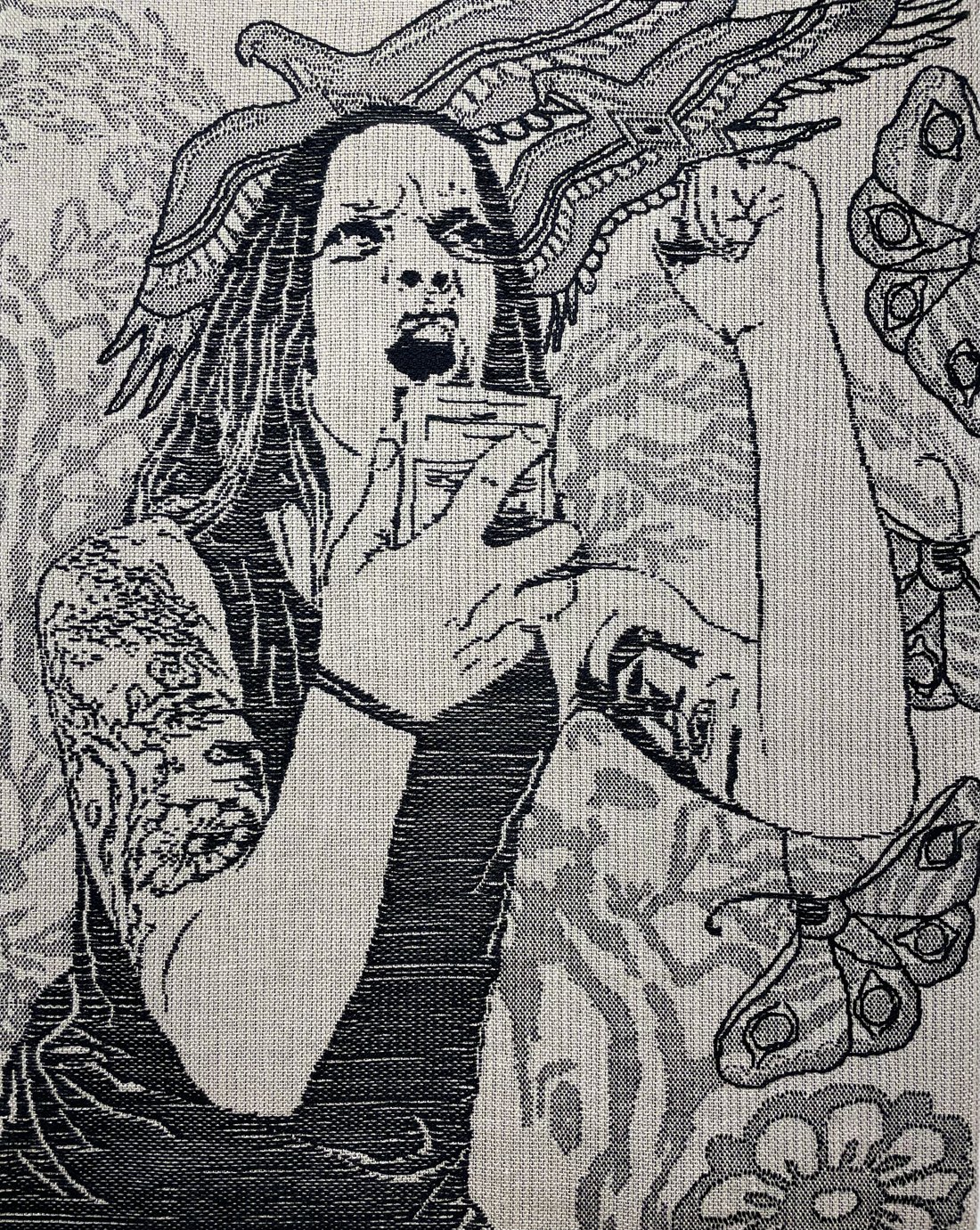

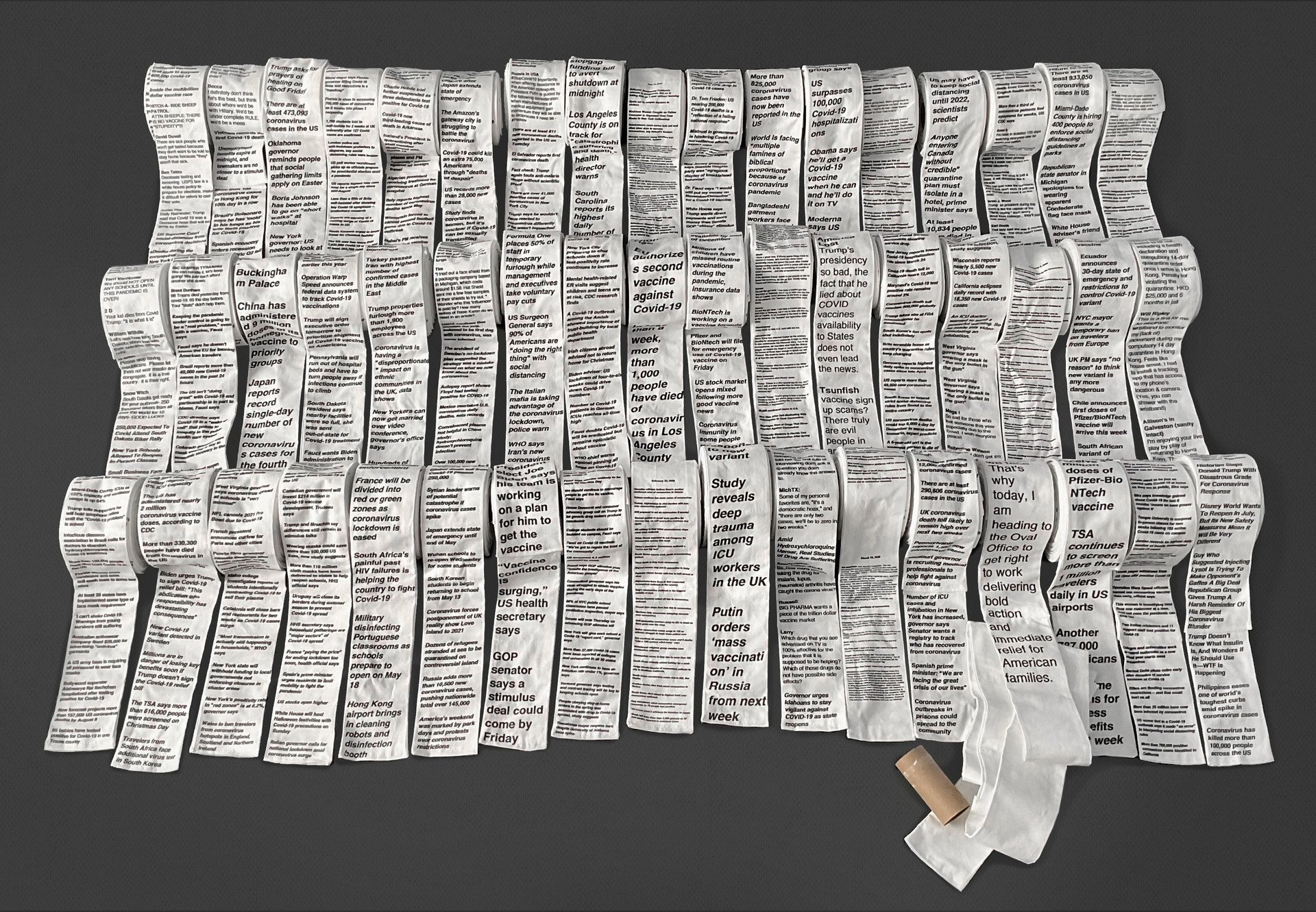

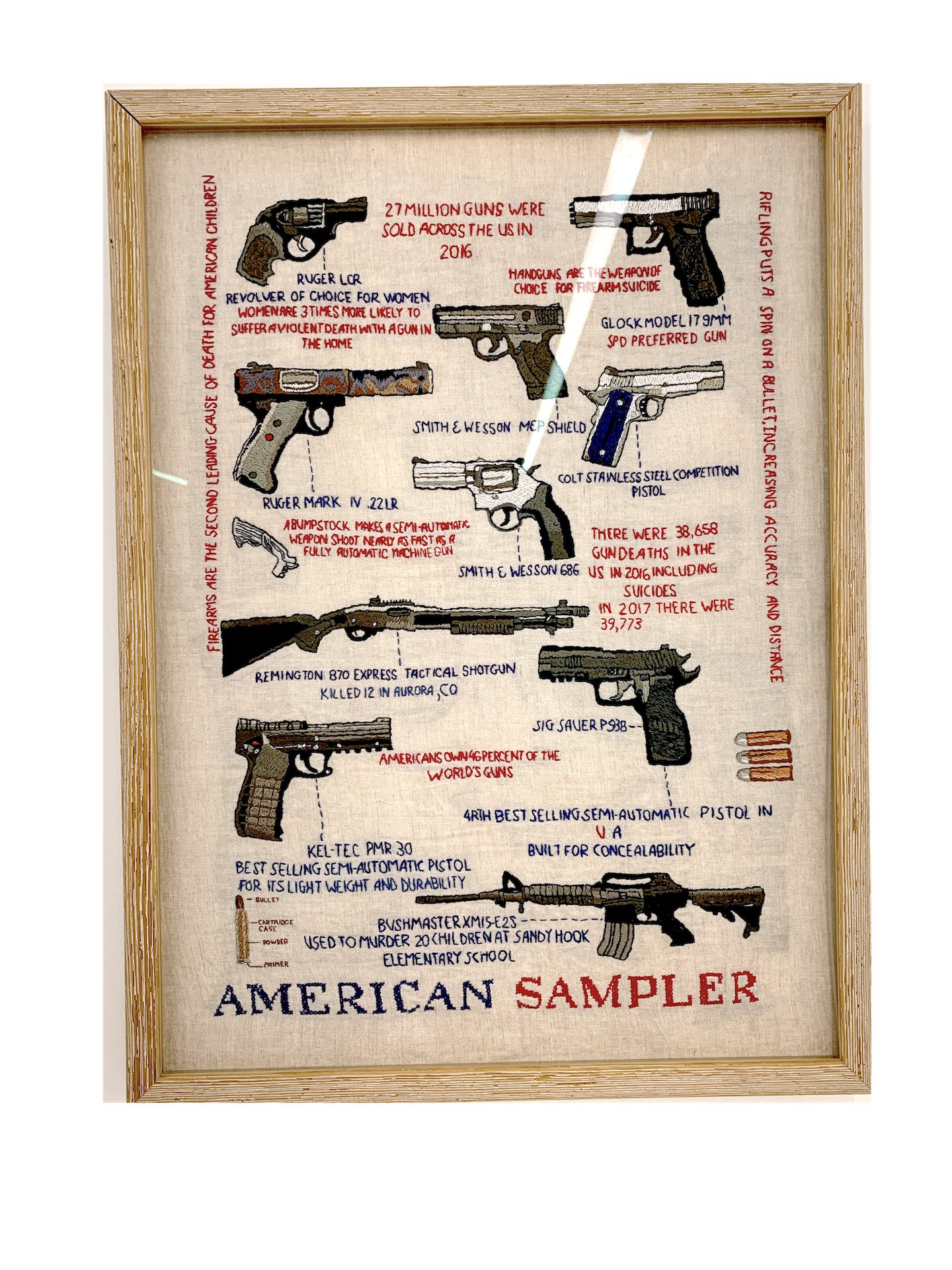

Addressing issues of gun control is Matthew Coté, who created a mixed media brooch shaped like the state of Connecticut with AR15 rifles and enamel representation of the 26 victims of the Sandy Hook tragedy. Also highlighting the role of guns in American society is Naomi Spinak, whose embroidered sampler displays the most popular guns sold in the nation alongside statistics about their usage. In figural, handwoven pieces, Cyndy Barbone presents timely, urgent messages about body autonomy, a message also addressed in textile works by Hazel Batrezchavez. Printing social media comments and news headlines from the first year of Covid-19 onto toilet paper, Nikyra Capson considers the toll of the pandemic, in particular the loss of lives. Also using toilet paper and reflecting on the impact of Covid-19 is Lynne Rigby, whose embroidery tracked the mounting human toll of the pandemic.